On the uses of the ‘happy hooker’

Sadie Slyfox, sadievolpone@gmail.com

Sadie is a brothel-based sex worker, Someone’s Daughter, and a pseudonym. She is a settler who lives and works on stolen Wurundjeri land. She tweets at @sadie_slyfox.

Abstract

This essay asks why, despite widespread recognition that all workers’ happiness can be appropriated in the service of capitalism, the happiness of sex workers is seen as exceptionally troubling and suspect. To address this question, it explores representations of the happiness (or unhappiness) of sex workers, embodied in the figure of the ‘happy hooker’. The essay tracks the emergence of this figure in the writings of feminists who campaign for the abolition of sex work, pop cultural representations of sex work produced by non-sex workers, and the cultural production of sex workers themselves.

Keywords

sex work, feminism, happiness, work, representation

FULL TEXT

“More smiles? More money. Nothing will be so powerful in destroying the healing virtues of a smile.”

-Silvia Federici 1975, 1

I exchange sexual services for money; I am a sex worker. As is the case with many jobs, sex work involves a degree of emotional labour—specifically, in my experience, a performance of happiness. This usually begins when I introduce myself to a prospective client in the lounge of the Melbourne brothel in which I work. When I first started sex work, I struggled with introductions, so I asked a colleague for advice. She suggested that I walk into the room with the same facial expression that I would wear as I describe my services, rather than allowing a client to see my face flicker into Sadie’s. Smiles have always been my default: if I am nervous, they tighten my expression to mask a quivering lip; when they are reciprocated, I ease more gently into the rhythm of a conversation. I smile at work because, at least for me, smiles sell. However, some smiles come of their own volition, jolting from my gut to Sadie’s face. Likewise, Sadie’s smiles often find me outside of work, when I remember an awkward moment in a booking, or a story told by another worker. I’m not sure how, or if, these smiles correlate with happiness.

Happiness – or rather, a performance of happiness – is demanded of workers across industries. For instance, in 2012 the management of the Royal Melbourne Institute of Technology (RMIT) received widespread criticism for issuing a new behavioural code demanding that staff display a “positive attitude” while they work (Preiss, 2012). RMIT’s injunction to smile was ridiculed by the National Tertiary Education union (Nette, 2012) and seen by some as an attempt to reframe “scholars, educators and public intellectuals … as point of sale customer service representatives” (Saltmarsh and Randell-Moon, 2014, p. 246). Indeed, displays of happiness have long been demanded of service sector workers and can be understood as an example of what Hochschild (1983) calls emotional labour—that is, the management of emotions as an unspoken and unremunerated component of waged work. While this is clearly an extraction of surplus value from workers, as Federici (1975) and many others have argued, it can also be a means of instilling acquiescence, particularly for those whose labour is feminised – that is, invisibilised and devalued.

Given the above, there is good reason to treat associations between happiness and work with suspicion. However, when it comes to sex work, such associations tend to elicit a special kind of scepticism, and sometimes derision. Because, as Grant (2014, p.146) puts it, “the public is groomed to expect a poor, suffering whore”, expressions of joy on part of sex workers tend to be rejected out of hand as a lie or product of false consciousness. At the other end of the spectrum is a liberal notion of sex work as a source of personal happiness and empowerment, which sex workers are constantly pressured to reproduce. In any case, the happiness of sex workers has been uniquely pathologised and politicised, and this affects how sex workers are represented by others and what is heard, and ignored, when sex workers speak about themselves.

This essay explores how this occurs, and what its effects might be, by reflecting on the ‘happy hooker’, a figure that is increasingly invoked in political debates on sex work, as well as cultural representations of sex workers. It considers how the happy hooker features, both explicitly and implicitly, in three bodies of texts: the writings of feminists who oppose the sex industry; pop cultural representations of sex work produced by non-sex workers; and the cultural production of sex workers themselves. This shows how, as others have argued, the happy hooker has been used to construct a false dichotomy between empowerment and victimhood, as well as to downplay the structural factors that naturalise happiness for some and deny it to others. It also shows how sex workers have taken up, subverted and rejected the happy hooker and related figures, developing complex, situated analyses of the role of happiness in work and activism along the way.

Happy Hooker #1: the victim’s Other

The happy hooker regularly appears in the writing and campaigning of those who regard sex work as a social ill that must be eradicated through the use of criminal law (Chateauvert, 2014; Mac and Smith, 2018). Feminists who share this view tend to identify as ‘radical’ and argue that ‘prostitution’ constitutes both violence against women and a form of slavery insofar as engagement in sex work can never be chosen freely by women under patriarchy and global capitalism (e.g. Jeffreys, 2009; Raymond, 2013). This analysis draws on a bio-essentialist view of sex as the foundational category of oppression (see Firestone, 1970) and an (incorrect) assumption that all sex workers are cis women. Accordingly, commercial sex is seen by anti-sex work feminists as an affront to the human rights of all women, not just sex workers (see Raymond, 2013, p.125). Those who reject their call for and approach to its abolition are labelled anti-feminists or liberal feminists who are more concerned with the personal choice and freedoms of individuals than dismantling the systemic exploitation of women as a class (see Bulbeck, 2005, p.65).

The happy hooker, according to anti-sex work feminists, is both a product and proponent of such liberal politics. Invariably gendered as ‘she’, the happy hooker is framed as a myth used to suppress more harrowing accounts of the sex industry, perpetuated by those who profit from it (see, for example, Bindel, 2017). Such accounts tend to locate the harm of sex work in the sex itself, often conveying this through gratuitous imagery and dehumanising language—for example, by reducing sex workers to body parts to be ‘rented’ and ‘fucked’ (e.g. Bindel, 2017; Jeffreys, 1997). Anti-sex work feminists commonly assert that such violent experiences are the norm, thus constituting the happy hooker, who appears to be spared from it, as the exception—a privileged minority that is afforded a degree of choice and autonomy unavailable to most (Raymond, 2013, p.19). Thus, any analyses and advocacy by those who are perceived as happy hookers can more readily be discarded as a product of ignorance or self-interest, as well as a callous betrayal of the silenced majority (e.g. Brunskell-Evans, 2017; Williams, 2017).

There are several problems with this construction. Firstly, by over-emphasising sex as a source and site of harm, anti-sex work feminists tend to downplay the structural forces that harm sex workers at both a systemic and everyday level (see Doezema, 2010). Meanwhile, their policy proposals risk exacerbating these harms by emboldening the authorities that execute them, including the police, migration officials, and the rescue industry (see Agustín, 2007; Butterfly, 2018; Mac and Smith, 2018). Secondly, both the happy hooker and her inverse, the unhappy prostitute, are ill-defined, and their constitution seems to have less to do with their material circumstances, and more to do with their political leanings. That is, when sex workers who might be deemed ‘real victims’ do not adhere to the abolitionist script, they are re-signified as happy hookers and accordingly dismissed (see, for example, Mullin, 2017). Finally, this classification also relies on dichotomies that separate choice from force and empowerment from oppression, when in reality these experiences are not so clear cut. Sex workers have long recognised this complexity and discussed choice and empowerment in ways that acknowledge their constraints and contradictions (see, for example, Nagle, 1997). The construction of the happy hooker as the singular, uncontested voice of sex workers only works by erasing this speech.

Happy Hooker #2: the high-class escort

Another variation of the happy hooker can be found in pop cultural representations of sex work, albeit with different attributes. Here, she is also feminised, portrayed as an independent woman breaking from cultural norms and feminist orthodoxies. However, rather than being admonished for this behaviour, she is celebrated for her resourcefulness and willingness to assert her sexual and economic desires. This is exemplified in the documentary Happy Hookers, which follows what is claimed to be a growing sociological phenomenon in which “young, trendy women in London … are turning to high-end escorting to finance their expensive taste for lavish goods” (SBS, 2017). This experience is also reflected in the television series Secret Diary of a Call Girl, which draws from the autobiographical writings of Belle de Jour (also known as Dr Brooke Magnanti), a former elite London escort (Showtime, 2017). Similar portrayals of ‘high class’ sex workers in pop culture can be seen in the television series The Girlfriend Experience, based on Steven Soderbergh’s film of the same name (IMDb, 2017a), and, closer to home, the television series Satisfaction, which follows the lives of sex workers connected to an up-market Melbourne brothel (IMDb, 2017b).

Despite their inaccuracies and stereotypes, texts such as these can offer an alternative to dominant representations of sex work as inherently harmful and sex workers as necessarily damaged and subordinated, which many sex workers might find validating and refreshing. They depart from the notion that one could not possibly choose sex work by depicting characters who make a conditional choice to take up sex work for a variety of reasons. Particularly in Satisfaction, the characters are not defined only as sex workers, but are given depth and dimension through consideration of their other identities—for example as mother, partner, and student. In some instances, their negotiation of these roles is explored in ways that trouble dominant representations of sex workers as unloving and unlovable. Finally, while happiness can be portrayed in simplistic ways, some texts more than others also attend to unhappiness in way that highlights stigma, rather than (perceived) pathology.

However, there is also plenty to critique, particularly in terms of what these texts fail to acknowledge. A key issue lies in the narrow range of experiences portrayed. Almost invariably, this variation of the happy hooker is white, cis gendered, socially and economically advantaged, and living in a metropolitan area of the Global North, although sex workers with such characteristics are only a small minority in a large and diverse workforce (see Renshaw, Kim, Fawkes, and Jeffreys, 2015; Scott, Minichiello, Marino, Harvey, Jamieson, and Browne, 2005). By constituting the happy hooker in this way, these texts tend to fuse happiness with privilege and notably whiteness (see also Ahmed, 2010), while remaining largely silent on the structural conditions that impact the differential experiences of sex workers along lines of race, class, and migration status (see Butterfly, 2018; DeCat, 2018). For example, although these shows are set in jurisdictions in which sex work is either criminalised or regulated by a licensing regime, seldom do they even approach a complex discussion about the effects of criminalisation on the lives of sex workers, let alone the uneven distribution of these effects (Haywood, 2016; Mac and Smith, 2018).

As exemplified by the texts cited above, pop cultural representations of sex workers that garner mainstream attention are overwhelmingly produced by non-sex workers. On the rare occasions that sex workers are consulted in the development of such representations, this tends to be in a tokenistic or exploitative way. This occurred in relation to the 2017 documentary television series Hot Girls Wanted: Turned On, which was a follow-up to the 2015 documentary film of the same name, both of which explored the supposed mainstreaming of pornography (Schlegl, 2015). Following the release of the television series, sex workers involved in the show accused the producers of using coercive interview tactics, and of broadcasting their personal information and pornographic work without their consent, thus compromising their anonymity and safety (Brown, 2017; Josephine, 2017). Another example concerns Top of the Lake: China Girl, a recent television series by celebrated Aotearoa/New Zealand director Jane Campion. In addition to the show’s racist depiction of Asian migrant sex workers (see Scarlet Alliance, 2017), sex workers also took issue with the approach to ‘consultation’ taken during its production. Campion had in fact spoken with representatives from Scarlet Alliance, the Australian peak body for sex workers, which, in response expressed considerable concern about some aspects of the series. Rather than accepting their critique, Campion simply ignored their advice (Hughes, 2017).

Happy hooker #3: a versatile weapon

Although sex workers’ voices may be ignored and appropriated in mainstream pop culture, there is a rich and continuing tradition of sex workers representing themselves in performance art, music, literature, film, critical writing, and many other modes of cultural production (see Chateauvert, 2014, pp.200-202). For instance, the UK Sex Worker Advocacy and Resistance Movement (SWARM) regularly publish zines created by sex workers, including editions that explicitly focus on sex workers facing particular kinds of compounded marginalisation (SWARM, 2017). Tits and Sass is a US-based current affairs website run by sex workers, for sex workers, which also prioritises writing that offers first-hand accounts of the intersections of whorephobia, racism, ableism, and other systems of oppression (e.g. de Long, 2018; F, 2018). Sex workers in Australia have shared written work, visual art, performance art, and more through self-organised exhibitions, conferences, festivals, and political demonstrations, as exemplified by the work of the sex worker art collective Debby Doesn’t Do It For Free (DDDIFF) (see Surtees, 2015) and protest events organised by local peer sex worker organisations. Sex workers have also taken to social media, using art, poetry, and direct political commentary to represent their work and their lives on their own terms, for an audience of sex workers and non-sex workers alike.

Fig. 1. Illustration depicting ‘the inquisitive stripper’. Created by Jacq the Stripper [2018]. From Instagram. https://www.instagram.com/p/BqcsVmkAkV1/

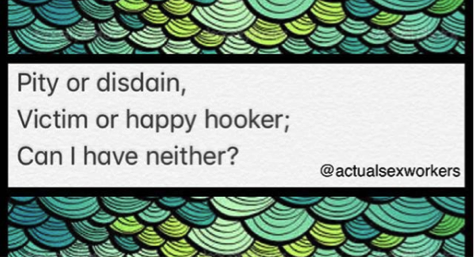

DDDIFF is a large and ever-changing collective of sex workers based in various settings and operating under different legal regimes, each of whom takes up a different ‘Debby’ moniker. Like Jacq the Stripper’s art, some DDDIFF pieces invoke happiness through satirical humour, or a staunch, sometimes joyful, refusal to be ‘toned down’ or to shut up. Conversely, some artworks seem to refuse happiness altogether, instead offering an account of what makes sex workers unhappy, as exemplified by Figure 2.

Fig. 2. Painting of a sex worker being accosted by various authorities. Created by Decriminalise Debby, published by Debby Doesn’t Do It For Free [2018]. From Instagram. https://www.instagram.com/p/BgzxnsZlYdY/

Similarly, sex workers of colour have critiqued, in Adrie’s (2019, n.p.) words, “empowered white sex workers”, for whom “sex work is fun”. As Adrie argues, not only has this subject position has been centred over others despite its profound exclusivity, but, in her experience, it factors into forms of lateral violence enacted by the “white, middle-class, educated women” who are able to take it up. This speaks to a broader problem that has also been pointed out by sex workers of colour and migrant sex workers, namely that public discussions about sex work tend to be dominated by white women, such as myself, and that our speech can and sometimes does reproduce the erasures and harms we purport to oppose (see DeCat, 2019; Lam, 2016). Relating to sex work through discourses of pleasure and positivity can sustain this dynamic by, inadvertently or otherwise, minimising space and tolerance for alternative assessments. As suprihmbé (2018, p.36), also known as @thotscholar, points out, discourses of positivity can factor into such erasures – in her words, “When we [Black women] worry aloud, when we critique, we are told we’re doomsayers … But people are suffering and dying, whether you wanna hear it or not”.

Conclusion

Fig. 3. An image of a ‘hooker haiku’. Created by Actual Sex Workers [2018]. Instagram. https://www.instagram.com/p/BhLktXhnE-X/

List of Figures

Figure 1 – Illustration depicting ‘the inquisitive stripper’

Figure 2 – Painting of a sex worker being accosted by various authorities

Figure 3 – An image of a ‘hooker haiku’

Reference List

Adrie. 2019. ‘Can You Not, Empowered White Sex Workers’. I Would Like You to Stop. Viewed May 29, 2019, https://www.canyounot.me/blog/2019/5/21/can-you-not-empowered-white-sex-workers

Agustín, Laura Maria. 2007. Sex at the Margins: Migration, Labour Markets and the Rescue Industry. London, UK: Zed Books.

Ahmed, Sara. 2010. ‘Killing Joy: Feminism and the History of Happiness.’ Signs, 35 (3): 571-594.

Bindel, Julie. 2017. The Pimping of Prostitution: Abolishing the Sex Work Myth. Melbourne: Spinifex.

Brown, Elizabeth Nolan. 2017. ‘Hot Girls Wanted: Exploiting sex workers in the name of exposing porn exploitation?’ Reason. Viewed May 2, 2017, http://reason.com/blog/2017/04/26/hot-girls-wanted-docu-series-exploits-se

Brunskell-Evans, Heather. 2017. ‘The Contemporary Cult of the “Sex Worker”’. Feminist Current. Viewed May 3, 2017, http://www.feministcurrent.com/2017/03/01/contemporary-cult-sex-worker/

Bulbeck, Chilla. 2005. ‘“Women Are Exploited Way Too Often”: Feminist Rhetorics at the End of Equality’. Australian Feminist Studies, 20 (46): 65–76.

Butterfly. 2018. Behind the Rescue: How Anti-Trafficking Investigations and Policies Harm Migrant Sex Workers, Toronto, CA: Butterfly Print.

Chateauvert, Melinda. 2014. Sex Workers Unite: A History of the Movement from Stonewall to SlutWalk. Boston, MA: Beacon.

DeCat, Nada. 2019. ‘The Racism of Decriminalization.’ Tits and Sass. Viewed May 20, 2019, http://titsandsass.com/the-racism-of-decriminalization/

de Long, Katie. 2018. ‘Kavanaugh’s Confirmation Will Kill Disabled Sex Workers Like Me’. Tits and Sass. Viewed December 20, 2018, http://titsandsass.com/kavanaughs-confirmation-will-kill-disabled-sex-workers-like-me/

Doezema, Jo. 2010. Sex Slaves and Discourse Masters: The Construction of Trafficking. New York: Zed Books.

F, Harley. 2018. ‘Deep In The Shadows: Working Trans Without Disclosure’. Tits and Sass. Viewed December 20, 2018, http://titsandsass.com/deep-in-the-shadows-working-trans-without-disclosure/

Federici, Silvia. 1975. Wages against Housework. Bristol: Falling Wall.

Firestone, Shulamith. 1970. The Dialectic of Sex: The Case for Feminist Revolution. New York: Bantam Books.

Frances, Jacqueline. 2017. The Inquisitive Stripper. Scotts Valley, CA: CreateSpace Independent Publishing Platform.

Grant, Melissa Gira. 2014. Playing the Whore: The Work of Sex Work. London: Verso.

Haywood, Deon. 2016. ‘What TV Show “The Girlfriend Experience” Gets Wrong About Sex Work’. Alternet. Viewed November 29, 2018, https://www.alternet.org/sex-amp-relationships/girlfriend-experience-wrong-sex-work

Hochschild, Arlie. 1983. The Managed Heart: Commercialization of Human Feeling. Berkeley and Los Angeles: University of California Press.

Hochschild, Arlie. 2013. ‘Can Emotional Labor Be Fun?’ In So How’s the Family? And Other Essays, edited by Arlie Hochschild, 24–31. Berkeley and Los Angeles, CA: University of California Press.

Hughes, Sarah. 2017. ‘Nicole Kidman Asked for a Part. Then it was Fun to Write a Sequel.’’ The Guardian. Viewed November 29, 2018, https://www.theguardian.com/tv-and-radio/2017/jul/08/top-of-the-lake-returns-nicole-kidman

Internet Movie Database (IMDb). 2017a. ‘The Girlfriend Experience.’ IMDb. Viewed May 15, 2017, from http://www.imdb.com/title/tt3846642/

IMDb. 2017b. ‘Satisfaction.’ IMDb. Viewed May 15, 2017, from http://www.imdb.com/title/tt1129029/?ref_=nv_sr_2

Jeffreys, Sheila. 1997. The Idea of Prostitution. Melbourne: Spinifex.

Jeffreys, Sheila. 2009. The Industrial Vagina. Abingdon: Routledge.

Josephine. 2017. Gia Paige After Hot Girls Wanted: Turned On. Tits and Sass. Viewed May 20, 2019, http://titsandsass.com/gia-paige-on-regretting-hot-girls-wanted-turned-on/#more-22710

Lam, Elene. 2016. ‘The Birth of Butterfly: Bringing Migrant Sex Workers’ Voices into the Sex Workers’ Rights Movement.’ Research for Sex Work (15): 1-4.

Mac, Juno, and Smith, Molly. 2018. Revolting Prostitutes: The Fight for Sex Workers’ Rights. London: Verso.

Mullin, Frankie. 2017. ‘In Full Sight: ‘The Pimp Lobby’ at the Amnesty AGM.’ Verso. Viewed May 10, 2019, https://www.versobooks.com/blogs/3162-in-full-sight-the-pimp-lobby-at-the-amnesty-agm

Nette, Andrew. 2012. ‘NTEU media Release: RMIT University Staff Oppose Management Overkill on Behaviour Standards.’ NTEU. Viewed May 15, 2017.

Nagle, Jill, ed. 1997. Whores and Other Feminists. New York: Routledge.

Preiss, Benjamin. 2012. ‘RMIT Academics Really Not Happy About Having to Be Happy at Work.’ Sydney Morning Herald. Viewed May 12, 2017, http://www.smh.com.au/national/education/rmit-academics-really-not-happy-about-having-to-be-happy-at-work-20120326-1vuob.html

Raymond, Janice G. 2013. Not a Choice, Not a Job: Exposing the Myths about Prostitution and the Global Sex Trade. Dulles, VA: Potomac Books.

Renshaw, Lauren; Kim, Jules; Fawkes, Janelle; and Jeffreys, Elena. 2015. Migrant Sex Workers in Australia. Canberra: Australian Institute of Criminology.

Saltmarsh, Sue and Randell-Moon, Holly. 2014. ‘Work, Life, and Im/Balance: Policies, Practices and Performativities of Academic Well-Being.’ Somatechnics 4 (2): 236–52.

Scarlet Alliance – Australian Sex Workers Association [Scarlet Alliance]. 2017. ‘We Don’t Know What Campion Means’. Facebook, August 10, 2017. https://www.facebook.com/scarletalliance.org.au/posts/we-dont-know-what-campion-means-by-her-statement-that-top-of-the-lake-is-beyond-/1578130765571316/

Schlegl, Kara Eva. 2015. Rashida Jones’ Porn Documentary ‘Hot Girls Wanted’ Only Tells Half the Story.’ Junkee. Viewed April 20, 2018, https://junkee.com/rashida-jones-documentary-hot-girls-wanted-only-tells-half-the-story/59323

Scott, John; Minichiello, Victor; Marino, Rodrigo; Harvey, Glen P.; Jamieson, Maggie; and Browne, Jan. 2005. ‘Understanding the New Context of the Male Sex Work Industry.’ Journal of Interpersonal Violence, 20 (3), 320-342.

Sex Worker Advocacy and Resistance Movement (SWARM). 2017. ‘Zines.’ SWARM. Viewed May 15, 2017, https://www.swarmcollective.org/zine/

Showtime. 2017. ‘Secret Diary of a Call Girl.’ Showtime. Viewed May 12, 2017, http://www.sho.com/secret-diary-of-a-call-girl

Special Broadcasting Service (SBS). 2017. ‘Happy Hookers.’ SBS. Viewed May 10, 2017, http://www.sbs.com.au/ondemand/video/11790403861/happy-hookers

suprihmbé (aka @thotscholar). 2018. give, an excerpt from the forthcoming thotscholar: a proheaux womanism primer. Chicago: bbydoll.

Surtees, Matilda. 2015. ‘Debby Doesn’t Do It For Free: Sex Workers Speak Up.’ Archer. Viewed November 30, 2018, http://archermagazine.com.au/2015/05/debby-doesnt-do-it-for-free-sex-workers-speak-up/

Williams, Janice. 2017. ‘Whether it’s Prostitution or the Holocaust, Deniers Are All the Same.’ Feminist Current. Viewed May 5, 2017, http://www.feministcurrent.com/2017/02/23/whether-prostitution-holocaust-deniers/

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivs 3.0 Australia License.

ISSN: 2202-2546

© Copyright 2015 La Trobe University. All rights reserved.

CRICOS Provider Code: VIC 00115M, NSW 02218K