“I’ll eat you up!”: Fears and Fantasies of Devouring Intimacies

Eva-Lynn Jagoe

Abstract

Through storytelling, this essay explores hunger and desire as it weaves fairy tale with theories of orality. Jagoe links an infant’s need for nourishment with the confusion of love that can morph into a devouring possessiveness. The motifs of eating, of taking in, and of containment are discussed in relation to Little Red Riding Hood, Maurice Sendak, Slavoj Zizek, and family memoir. From the ghoulish imagination of children and fairytale, to the sexual complexity of adolescence, and on to the limits and capacities of maternal love, Jagoe interrogates an intimacy that nourishes instead of devours, that contains instead of consumes.

Keywords

Storytelling; Orality; Fairytale; Memoir; Motherhood

FULL TEXT

My family ate my twin. Shortly after he and I were born, my parents fell on hard times. Faced with so many hungry children, they checked to see which one of their round babies was fattest. He was, just by a bit. So they roasted him at 400°.

“Even me, did I eat him?” I asked my siblings, who told me the story.

“Yes, we all sat around the dinner table and you licked your fingers. That’s why you’re fat now.” And then they would pinch my waist and pretend to bite my arms as I squealed with pleasure and fear.

I tried to erase the image of his pudgy legs, his soft baby belly, crisping in a hot blaze of fire as he became our suckling roast. I escaped that death but, as the extra mouth to feed, I also caused it.

For the rest of my overfed childhood, I missed my other half and wished I hadn’t been such an insatiable baby. To love people seemed like a delicate balance of getting what I needed from them without eating them up. Because if I devoured them, I’d be left with even more of a gaping void than the one the hunger had originally sought to fill.

The tall tale that my siblings told me seems particularly macabre, but it’s not so different from the many fantasies and fairy tales that permeate our culture. Parents, lovers, children, wolves, witches, and monsters titillate and threaten with the charged phrase, “I’ll eat you up!” It’s both a happy ticklish delight and an ominous menace. The realm of love and intimacy tastes of the flesh and blood and drool and tears and milk of each other. But where does it stop? How much can we give and take so that we are each nourished but not eaten up? The trick is to maintain happy intimacies in which we are contained but not consumed, delighted but not devoured.

It’s hard to get that ratio right, though. Because devouring is seductive, and seduction is devouring. Yes, of course “Little Red Riding Hood” ends with the wolf’s comeuppance, but most of the story is about his wily lure. When he meets Little Red, he professes admiration for her flashing red cloak and encourages her to enjoy herself in the wild wood. How different from her authoritarian mother, who admonishes her to be polite, constrained, and careful! The wolf makes her feel not like an undisciplined child, but rather a delicious creature whose desire for attention should be indulged. So when she exclaims about those big eyes, ears, hands, and mouth, the charming beast gives the response that she most hopes for but fears: “the better, my dear, to see you… to listen to you… to touch you… and… to eat you up!” His rapacious attention is dangerous but oh-so-thrilling. And irresistible too, because they confirm to the girl that, despite her mother’s admonishments, she is indeed palatable exactly as she is.

As Little Red grows, she’ll probably learn that there are plenty of hungry fellows out there, all of them willing and eager to eat her up.

My first big bad wolf ate me up when I was 16. He was an airplane pilot, but I got to control the direction of his motorboat across the blue waters of the Mallorcan sea. My kid cousins were heaped in the back as I stood at the helm, acutely aware of the blonde and silver hairs on his chest, his Rolex and wedding band glinting in the sun, his gaze taking in my tanned belly.

Back in Barcelona, my body was looked at with less admiring eyes from the women of my mother’s family. I was foreign—my height from my American father, or maybe a product of my upbringing in a land of nutritional excess. My shape was unfamiliar to these Spanish relatives, who spoke in judgmental and incomprehensibly antagonistic tones about my long legs, rounded hips, loose limbs. I heard rebuke and rejection in my mother’s “I don’t know what you do to men!” Did she really not know? Did she not see in me what they saw? Did she just see fat and gangliness where they saw voluptuous willowiness?

I now get that my mother was also issuing a warning, one that spoke of her lived knowledge of how men can treat girls. But like Little Red, I was in no mood to accept maternal injunctions. Men found me sexy! They paid attention to me, they looked at me, and I felt powerful as we flirted. Like Miranda gazing from the shore at all the men who shipwrecked their way into her world, I was excited by their existence. “O, brave new world that has such people in’t!”

So when my aunt’s husband said he would take me back to the hotel on his motorcycle, I wasn’t going to be held back by the apparent uneasiness of the other adults. When I snuck back into my room a couple of hours later, my 14-year old cousin was awake and asked me where I had been. We stood in the moonlight whispering. I told her he had taken me to the beach, and angled myself so that she couldn’t see the scratches and dirt on my back.

Maybe I didn’t tell her because she was still a girl, and I didn’t want her to know that her dashing uncle was a predator. Or maybe because I didn’t have the words for it, my Spanish hardly up to the task. When I think about it now, I say it in English, “he ate me out.” But it was not just that I didn’t have the linguistic ability to say it; it was also that I couldn’t map it on the spectrum of my sexual knowledge at the time. My mother had made it clear to me that men always want one thing, and that their need for it is so uncontrollable that it is up to us women to protect ourselves. So did it count as a sexual act if there was no penetration or ejaculation? He hadn’t taken off any clothes. How to define his laying me down on a rock and putting his head between my legs? Was it something that he wanted, or something that I had unknowingly elicited? Who was taking, and who was giving? Is the power in the eating, or in the being eaten?

My inability to understand and answer these questions did not just stem from the fact that I was an inexperienced girl. I think he, in his philandering pilot life, had drawn strict and arbitrary lines around what was acceptable. Maybe if I had answered his phone calls afterwards I would have found out the parameters: fuck only certain orifices, or eat but don’t get eaten. These kinds of caveats seem like so many bets hedged, but they are also constitutive of how each of us defines intimate acts.

Take, for instance, the strange sexual parameters of philosopher and cultural critic Slavoj Zizek. You would think he, so psychoanalytic and world-wise, would be comfortable with oral and anal practices. His body, after all, is so unmistakably a body as he gives his lectures, gesticulating and twitching, sweating and spitting. But he is remarkably reticent to share his body, as evidenced in an interview with Decca Aitkenhead that was published in The Guardian on June 10, 2012. There he answers questions about Hegel by talking about his own sexual limits:

I am very—OK, another detail, fuck it. I was never able to do—even if a woman wanted it—anal sex. You know why not? Because I couldn’t convince myself that she really likes it. I always had this suspicion, what if she only pretends, to make herself more attractive to me? It’s the same thing for fellatio; I was never able to finish into the woman’s mouth, because again, my idea is, this is not exactly the most tasteful fluid. What if she’s only pretending?

Zizek, one of our contemporary society’s most voluble talkers, has no problem ejaculating words into his listeners’ ears. Yet from his penis comes another substance, “not the most tasteful” one, which he will not release into a woman’s mouth or anus. Of what is he so wary? One of the definitions of “attraction” is “the action of drawing or sucking in”. So it could be that he distrusts being sucked in by a woman pretending that she likes to suck him in. Or, on the other hand, it could be that he doesn’t fear that his cum isn’t a “tasteful fluid”, but that it’s too tasty, and that once she gets a taste of him, she’ll eat him up.

Zizek and the pilot are the same generation. I know in my gut that my predator wouldn’t have asked me to perform oral sex on him. In her latest book, Girls and Sex, Peggy Orenstein talks to teenage girls who consider blow jobs to be the thing they do when they don’t want to have sex, when they feel they owe the guy something, or just as part of making out. They don’t expect reciprocity, and in fact, feel that it requires a high level of trust and commitment to let a man perform oral sex on them. When I was young, my friends and I thought of blow jobs as an extreme act that came after a sexual penetrative relationship had steadied. To take a guy into my mouth was a lot more intimate than into my vagina, and his mouth was much more personal than his penis.

I didn’t continue seeing the pilot because he scared me. I didn’t understand if he had raped me, or if I had been given something I wanted. Did his wife allow him to eat her? If she didn’t (and she obviously didn’t—not her, my sweet and infirm Catholic aunt!) then did I hold a knowledge and a power over her, and over him? He did, after all, risk his marriage and his reputation, to get a taste of me, and I gave it to him. With his big mouth, he showed me that I was delicious. And that was something that my mother had never been able to give me: the feeling that I was irresistible and delectable.

It wasn’t just me that my mother found inedible. She didn’t eat much of anything. When I was 11, she developed a spasm in her throat. Her oesophagus would constrict around any food she tried to swallow. She would choke on steak, spitting chewed pieces into her napkin. Potatoes, even mashed, stuck in her throat. It wasn’t about soft or chewy, hard or stringy; it was something less predictable about density, consistency, and taste. She would sit at the dinner table, silently crying, as my father attempted to keep the family conversation afloat.

She went down to 92 pounds that first year, as she went through various traumatic experiments of oesophagus stretching, drug treatments, and psychoanalysis (which she rejected after about a month: “it’s so stupid, they just want to blame everything on the mother”). She only started to recover under a regimen of Valium and occasional sips of holy water from Lourdes. She regained her weight once she decided to allow herself whatever she could swallow. Mostly delicate sweet pastries and thickly buttered thin toast, slices of cheese and finely mashed tuna salad. Nowadays, she no longer feels hunger, but is often weak or shaky because of blood sugar drops and spikes.

This debilitating psychosomatic illness had its benefits. It got her out of going to endless dinners and social events with my philanthropist father. She was free from the scrutiny of the American women who towered over her at cocktail parties, tossing back their martinis and canapes while she sipped at a tonic water. She could stay at home and watch PBS, or tidy her clothes. I would say that it gave her more time to be with her last child still at home, but that’s not how I remember it.

Instead: I would burst into her room, diving onto her bed with my belly full of the Doritos or chocolate chip cookies that I had wolfed down when I got home from high school. She would be reclining on her chaise longue next to the window, her head propped by her hand, eyes closed, a cup of tea and a few shortbread biscuits on the little table at her side. She would smile at my stories of Regina and Anne fighting over a KitKat, or of the saying that the nuns told us about why we should avoid premarital sex: “it’s like potato chips, you can’t have just one.” Sometimes she would interject a comment (“How do they know? They’re nuns!”), but after a few minutes she would say that I was tiring her with my talking. I would quietly close the door behind me, feeling like my mouth was too big and too American, but the next day I would crash in again, unable to stop trying to enliven her.

A couple of decades later, when she would see me kissing my babies voraciously, my mother would say the Spanish refrain, “cuando son pequeños, te los comerías a besos. Y cuando son mayores, te arrepientes de no haberlo hecho” (when they’re little, you could eat them up with kisses. And then when they get older, you wish you had). I think she was genuinely curious about my consuming love for my children, and that, in quoting that old wives’ saying, she was trying out the words of women who can’t control their maternal hunger for their children. I didn’t totally recognize myself in the refrain. I did find their fat little cheeks and toes delicious, and would eat them up with my kisses and take in their scent with big gulps of breath. But they were also eating me up. My sons got fatter and heavier as I got thinner, the blubber sucked out of me as I lay like a nursing seal, giving them the nutrients they needed to thrive.

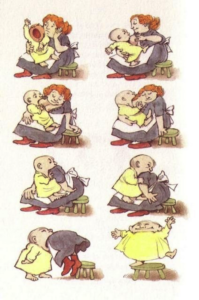

There’s a sketch by Maurice Sendak that is the opposite of my mother’s refrain (Sendak 1992, 75). In it, a screaming baby is soothed by suckling at his mother’s breast. He gets bigger and bigger as he opens his mouth wider and takes in more of the breast, then her head, then her whole body, until he is a happy fat child standing alone on the stool that she had sat on.

Sendak, Maurice. Illustrator to I Saw Esau: The Schoolchild’s Pocket Book, 1992

This image circulates on breastfeeding blogs, striking a chord with the new mothers who feel that they are being consumed by their insatiable little babies. Sendak portrays both the necessary selfishness of the child and the unconditional love of the mother, and the danger of giving free rein to either.

There’s a different ratio that needs to be maintained. A mother’s role is to give, but also to take away; to provide sustenance, and to teach limits. Not too much, not too little, but just right: that’s what a mother and child negotiate as they feed their inexhaustible love. Sendak represents this beautifully in his most famous book, Where the Wild Things Are, which I read to my son hundreds of times. It was always at dinner time. I would put a peeled and cored pear half on his high chair tray. His face, covered in peas and cereal, would light up as he stuck his thumb in the little hole I had cut out of the middle so that it wouldn’t slip out of his too tight clutch. I would open Where the Wild Things Are, and read him the story of a mother and child who work through the pleasures and perils of eating and of being eaten. Max is sent to bed without dinner because, at the end of a day of mischief in his wolf suit, he threatens his mother with “I’ll eat you up!” In his bedroom, he is unrepentant, and his anger dissolves the walls so that he sails away to “where the wild things are”. There, he proves that he is even scarier and more full of romp than they are, and is crowned king. When he tires of their wildness, he sends them to bed without their supper.

But it’s tiring to be so wild, and Max is “lonely and wanted to be where someone loved him best of all”. The wild things cry “Oh please don’t go—we’ll eat you up—we love you so!”. Ah, the tables have been turned! The wild things use the same threat that Max made to his mother, but this time it is attached to expressions of need and love. They are panicking, scared of being unloved and abandoned. Like the voracious breastfeeding child, they would consume their ruler in their hunger to have all of him. To keep him close and not risk separation.

Max, however, has learned the lesson taught to him by his mother, and knows that sometimes love is about limits. She makes it clear: he can’t eat her. But that doesn’t negate the fact that she is the one who “loves him best of all”. So he knows how to respond to the wild things’ hunger, and does so in one word that takes up the whole page: “No!”. They gnash their teeth and bare their claws, but he leaves them and returns to his room, where he finds his supper waiting for him. “And it was still hot.”.

And with that, I would close the book and my son would wag his head happily and hold his arms up for me to pick him up. I’d scoop him into my arms and growl “I’ll eat you up” as he sucked my chin and smeared pear chunks into my kissing mouth.

Oh, but it’s sad! Those wild things are so deliciously enticing, and game for rumpus. They let Max be their ruler, and do whatever he commands. So what have they done wrong, that he would leave them like that? Their wild love is not, unfortunately for them, what he needs, much as it tempts him. It’s delectable but dangerous to be amongst creatures that could, at any moment, gobble him up. So he returns to his mother and the walls of his room, where he is not a hero or a leader, but a contained individual. He is diminished but held, hungry but not devouring. He has learned that saying “I’ll eat you up” also means “I love and need you”, but that he is not allowed to actually devour his loved one. And he is comforted by less than he thought he needed, the soup an adequate substitute for the flesh of his mother.

It’s not so awful that my older siblings made up that story about eating my “twin”. I was their baby sister, after all. They sucked on my pudgy baby feet and fingers as I crammed them into their mouths. They let me gnaw toothlessly on their chins and noses, and wiped off the drool and vomit that I smeared on them. In the face of a mother who had little hunger for us—who found our hunger off-putting—we nibbled at each other, learning what was edible and what was not, learning the limits of each other.

References

Opie, Iona and Peter. Orenstein, Peggy. Girls and Sex: Navigating the Complicated New Landscape. New York: Harper Collins, 2016.

Sendak, Maurice. Illustrator to I Saw Esau: The Schoolchild’s Pocket Book. Edited by Iona and Peter Opie. Cambridge, MA: Candlewick Press, 1992.

—–. Where the Wild Things Are. New York: Harper Collins, 1963.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivs 3.0 Australia License.

ISSN: 2202-2546

© Copyright 2015 La Trobe University. All rights reserved.

CRICOS Provider Code: VIC 00115M, NSW 02218K