Section 1

The Re-Producing Womb-Matrix: reflections on an organ as a site of socio-political contestation through a discussion of print-based artworks

Angelica Harris-Faull

Abstract

This paper will present insights from my archival research on seventeenth century print and textual representations of the womb. These insights inform my print-based artworks which explore the womb as a site, or space of ongoing socio-political contestation. The uterus, or ‘matrix’ from Latin, refers to an original source. Within printmaking terminology the plate is conceived as the matrix, the base from which multiple generations of print can be made. I approach the matrix (womb and plate) as a morphing and creative source. Historically technological advances in western printmaking are linked to the proliferation and standardisation of knowledge through the production of reproducible books and printed material. The expansion of the printing press in the seventeenth century Europe resulted in an explosion in the production and distribution of texts on anatomy, reproduction, and bodily ideals. Women’s bodies, their internal and external bodily spaces, in printed material were positioned in accordance with prevailing medical, philosophical and moral ideas on reproduction. This paper will explore how the reproductive potential of printmaking could destabilise and diversify historical socio-cultural understandings of women’s womb as a site of contestation? In presenting prints from the seventeenth century and my own linocut based installation and video works I will consider how the reproducible nature of printmaking could actively subvert perpetuated conceptualisations of women’s bodies. This paper will draw on academic Karen Barad’s suggestion that critical engagements across and through time and locations can open new insights and modes of negotiating contemporary concerns.

Keywords

womb-matrix; socio-cultural understanding; print; print artwork; women; socio-political contestation

FULL TEXT

Introduction

The uterus, or womb, is an organ which forms part of the female reproductive system. The uterus is not always present in a female body, it can be present in bodies which align with diverse genders. Furthermore, it is not necessarily related to concepts or experiences of self and or gender. The uterus is, however, laden with metaphor-meaning and often associated with stereotypical, traditional western concepts of being a ‘woman’, and the womb is considered the primary site of gestation and reproduction. The uterus intersects political, governmental, social, media and familial discourses and is a site of socio-political contestation. The womb is a complex, tangled and temporal site of exploration of this article and my broader research. My research situated printmaking processes are informed by interpretations of seventeenth-century English print-based representations of the female reproductive body. I approach the matrix, which includes the womb, uterus and generative printing surface, as a morphing creative source.

I engage with a multiplicity of researcher positions and voices. I am positioned in, as I use my own body and experiences in making artwork. In addition, I am critical of weaving differing modes of working through and with historical and contemporary discourses that consider representations of female bodies. Self-reflexive perspectives are drawn on to ground these researcher positions and relations (Bryant 2016, 16-18). I also take lead from auto-ethnography: a process that “seeks to describe and systematically analyse (graphy) personal experience (auto) in order to understand cultural experience (ethno)” (Ellis, Adams and Bochner 2010, sec. 1, para. 1). My broader research is grounded in an inclusive feminist methodology. I seek to foreground a recognition and acknowledgement that there are diverse experiences and cultural and temporal understandings of the term ‘woman’. I acknowledge my position and privilege as a white, cisgendered individual who identifies with the term ‘woman’.

My central focus is an exploration of printmaking practice as a mode to destabilise and diversify historical socio-cultural understandings of women’s reproductive bodies. This article has a specific geographical and temporal focus; it engages with language from the seventeenth century through printed midwifery texts from England. It is western in focus. Karen Barad’s scholarship will form a theoretical basis, specifically her suggestion that critical engagements across and through time and locations can open new insights and modes of negotiating contemporary concerns. I propose that research-led printmaking practice, with a focus on the potential to repeat, over-print, misprint, ghost print and re-carve, can open a conversation between different time periods.

Thinking with Diffraction and Affect

Barbara Baird cogently suggests “histories are active constructions of the past which play a key role in constructing the present, both discursively and materially” (Baird 1998, 324). Texts, language, bodily representations, concepts of ‘womanhood’, time, printed matter and embodied experiences within my research are all entangled and interwoven. Consideration of other temporal states are not neutral; we carry our present self, our methodologies and our inky printing rollers with us. Two key theoretical frameworks, diffraction and affect theory, are drawn upon to facilitate thinking with temporality and embodiment, seventeenth century texts and practice-led creative research.

Karen Barad, working across new materialism, feminist philosophies and theoretical quantum physics, offers a re-consideration of matter, materiality, agency and a de-centralisation of the human (Barad 2007). Diffraction is a concept within physics that Barad, building on the work of Donna Haraway, has extended as a methodological tool. It describes an occurrence where waves (such as light or water) pass through an opening or around an object which in turn acts to alter the wave patterns. For example, as water comes into contact with and moves through a harbor there is a resulting shift in the visible wave pattern. The water and the harbor mingle and touch, as matter rubs and collides against matter. In this process, there is an often observable trace as the waves bend in relation to the harbor. In addition, Barad and Haraway recognise that the researcher, or in this case artist, and technology, are involved and implicated in the production of knowledge (Barad 2007, Haraway 1997, 583-585). As Baird articulates in the opening quote, histories are made; they are ‘active,’ ongoing and ‘constructed/ing’ phenomena. In addition, Barad foregrounds within diffraction a notion of differing temporalities being carried together, as an ‘inheritance and indebtedness to the past as well as the future’ (Juelskjaer and Schwennesen 2012, 13). Being sensitive and oriented to phenomena is central to my (ongoing-growing) understanding of diffraction as a methodological approach.

Working with diffraction offers a shifted mode of understanding and making meaning in the world, through the active observation of differences (or occurrences), specifically how they are made and the ripple effects of their presence. Iris Van der Tuin (2011, 23) in responding to Barad’s theory, effectively explores diffraction as a writing and thinking tool, as it “entails refraining from isolating philosophies, in their time…or as closed wholes.” Diffraction, here, akin to the work undertaken by Van der Tuin, offers a critical and creative mode of developing insights through an interweaving of the practice and materiality of making art with re-reading historical and contemporary texts in relation to and with the body.

Comparatively, affect theory can be understood as a broad theoretical approach to considering emotion, embodiment and notions of being in the world as constellations or relationships of phenomena through time. Gregory J. Seigworth and Melissa Greg (2010, 1) in their introduction to The Affect Theory Reader suggest that “affect is found in those intensities that pass body to body (human, nonhuman, part-body, and otherwise), in those resonances that circulate about, between and sometimes stick to bodies and worlds.”

Seigworth and Greg’s articulation of affect speaks to new materialist theoretical impulses which look beyond humanist notions in an acknowledgement of matter and the agency of matter. This article focuses on Sara Ahmed’s notion of affect, as “what sticks, or what sustains or preserves the connection between ideas, values and objects” (Ahmed 2010, 29). I draw upon Ahmed’s notion of ‘stickiness’ as a thinking tool, to consider the affective register of historical objects. Drawing on Ahmed’s theorisation of affect and Barad’s work with diffraction facilitates critical reflection on the role of the researcher, or maker, within the production of academic and practice-led research.

Bodies Through Time

The early modern period in the western world, approximately the fifteenth to late eighteenth centuries, witnessed rising production and translation of texts on anatomy and reproduction made via the mechanical printing press. The human body was conceptualised in this period through a complex intersection of diverse discourses, including philosophical treaties, religion, folklore and published popular printed material (as potential entry points to the field, see for example: on popular printed material: Fissell 2004 and Gowing 2003, on the socio-cultural understandings of the body: Kalof and Bynum 2010, and on intersections of religion, philosophy and the body: Porter 2003). Furthermore, the growing fields of medicine and anatomy were recorded, and often illustrated, within printed texts (Sawday 1995). Understandings of the human body in the early modern period were often informed by older medical and philosophical thought. For example, the humoral system or theory, practiced and considered within Ancient Greek medicine, involved four liquids thought to constitute the body and ideally exist in equal balanced parts (Arikha 2007, 8). These western notions of (ideal or perceived medical normative) bodily states, persisted through the early modern period and imparted sticky residues on understandings of female bodies. One such residue is visible in understandings of menstruation in the early modern period, as a purging and expulsion of excess fluids which could otherwise lead to ‘un-balanced’ humours within female bodies. As historian Patricia Crawford (2014, 25) writes, “many seventeenth century physicians followed Hippocrates’s dictum that the womb was the source of a thousand ills to women.”

Throughout the seventeenth century in Europe, sociocultural shifts occurred including the development of obstetrics as a profession (Ammer and Manson 2009, 288). Male midwives entered traditionally female-led spaces, shifting traditional birthing practices and the uses of women’s self-knowledge. While there are two records of female-authored early modern midwifery texts, one by Jane Sharp from England and the other by Louise Bourgeois from France, the field was predominately male as acknowledged by historical scholarship, including work by Laura Gowing (2012) and Elaine Hobby (2001). Within the early modern period there was an increased production of accessible midwifery or anatomical texts in English which, as Hobby writes, “sold well—The Byrth of Mankynd, for instance, passing through at least eleven editions between 1540 and 1654” (Hobby 2001, 210). Women’s bodies in midwifery texts were contested sites where social, cultural and political ideals were carved and printed into illustrations and medical explorations of the female body.

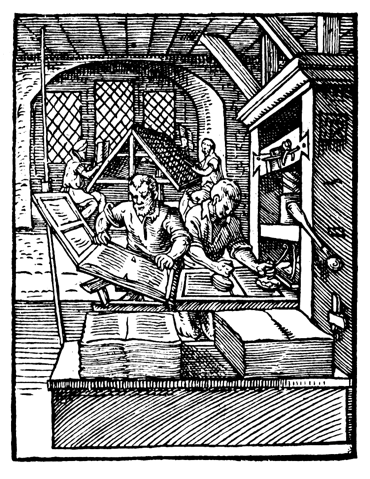

Figure 1: Thomas Chamberlayne, The complete midvvie’s practice enlarged, 1680,

Copy from Wellcome Institute for the History of Medicine Library, London.

Accessed via Early English Books Online, National Library of Australia.

In 2019, approximately four hundred years later, bodily choices, specifically reproductive rights, continue to be legislated, politicised and critiqued. In Australia, each state and territory currently prescribes differing medical and criminal legislation on abortion. Contemporary Australian laws, specifically abortion laws, continue to be shaped by ongoing colonial, Commonwealth practices, and are based on English law. The English Offences Against the Person Criminal Act, dated from 1861, can be seen as a foundational statement on abortion. It states that:

“Every woman, being with child, who, with intent to procure her own miscarriage, shall unlawfully administer to herself any poison or other noxious thing, or shall unlawfully use any instrument or other means whatsoever with the like intent…be guilty of felony, and being convicted thereof shall be liable . . . to be kept in penal servitude for life” (Offences Against the Person Act 1861, Attempts to procure Abortion, 58).

The often-contrasting contemporary state and territory Australian laws outline if abortion is legal, the timeframe in which an abortion can be obtained, and the number of healthcare professionals required for procedure approval. At the time of researching this article in 2018, the only state-run clinic that offered abortion procedures in Tasmania closed its doors (Burgess and Glumac 2018). Individuals undergoing an abortion procedure were required to travel to mainland Australia. While on a global stage in 2017, President Donald J. Trump reinstated the Golden Gag Rule restricting any overseas organisation, actively receiving American aid money, from providing information on, or abortion services (Darroch 2017). Such legislative, political, social and cultural structures and discourses impact the lives of individuals, and in particular bodies with female reproductive organs.

The Womb-Matrix

The mechanical process of printing and concepts of the womb were curiously linked in the English seventeenth-century. The etymology of the word ‘matrix’ witnesses a convergence of meanings. From the fourteenth-century it is associated with the womb, or uterus, it is also rooted in the Old French ‘matrice’ (womb), the Latin ‘matrix’ (pregnant animal) and the Late Latin ‘mater’ (original source and mother) (Oxford English Dictionary, n.d). Intertwined within the history of the word ‘matrix’ are ideas of gendered reproduction, it is evocative of a site or carrier and matter which is produced from that site. Within printmaking terminology, the plate is also called a matrix. It is the base, or surface, from which generations of print can be produced. The matrix in printmaking is intimately linked to concepts of material (textual and image-based) reproduction, with western historical origins in the development of cast metal letter type (Chamberlain 1972). The etymological histories of printmaking matrices and the womb-uterus as a matrix here collide.

Figure 2: Meggs, Philip B. A History of Graphic Design.

John Wiley & Sons, Inc. 1998.

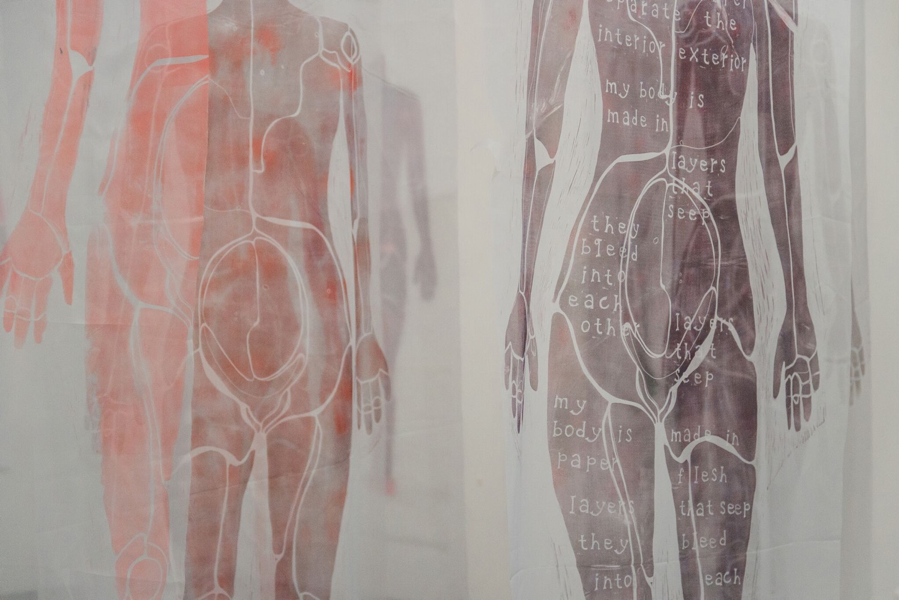

Figure 3: In Body, in time, lino print on fabric,

Gallery 1, Trocadero Art Space, 2018.

Image credit: Matto Lucas

Figure 4: In Body, in time, lino print on fabric,

Gallery 1, Trocadero Art Space, 2018.

Image credit: Matto Lucas

Printing and Re-Printing the Body

In Body, in time (figure 3 and 4) presents a series of printed transparent bodies which hang side-by-side; they repeat and repeat. These printed bodies emerge from a single matrix (or lino plate) which is rolled with ink and printed by hand, pressed into fabric. This lino plate mirrors the size of my body. There is a power in repetition. It can confront a viewer with mass, which can highlight prevalent practices, thereby facilitating awareness, and or critique. The use of the printing press and traditional relief methods is purposeful, as it connects my work to a historical epoch and a language of printmaking. It also recognises the complicity of these technologies in propagating specific textual and image-based representations of female bodies. In addition, in my artwork I reinterpret and make both visual and textual forms. The printing press has, in effect, enabled repetitions through time of specific ideas about, and images of, female bodies. I employ these historical print-based techniques to draw attention to past iterations of representational modes and consequential imprinted power saturated discourses.

This is a sticky point—how do I move, or make, within my print-practice led research, beyond a medicalised bodily interior, the omnipresent western medical human-interior maps. The matrices I make are layered with historical anatomical carved and printed lines that are drawn into the present. The mapped-body lines draw one’s attention to the methods by which the human body, and specifically the female body, is ordered and dissected anatomically, through language and sociocultural practices. These prints draw the historically represented body into critical observation by tracing how bodies have been understood through medical-anatomical enlightenment practices of segmenting, labelling and creating bodily hierarchies. The re-presentation of historical notions of women’s reproductive bodies in the present through the making of print-based installations facilitates recognition of past beliefs consequently enabling a critical re-observation of contemporary notions. Drawing attention to systems and patterns of representation can be considered one step in a process of destabilising and complicating existing beliefs.

Printmaking evokes tactile material languages, it can be articulated through varied foci, including technical process, material, image generation and histories. The lino prints, developed through this research, resist a technical printmaking convention of smooth and consistent inked forms. Instead the inky blotches and constellation-like marks form traces of temporality and show my labour: the lino block and my body interacting. Relief printmaking (processes including lino or wood carving) can be practiced today in modes which are similar to historical printmaking practices. Histories of print technologies and practices in western print discourses are often linked to and founded on the Gutenberg press, however I acknowledge that this is only one mode of negotiating developments within printmaking. The mechanically printed word emerged in Europe, in the fifteenth century, as Johannes Gutenberg developed a structure capable of holding inked movable type which could be pressed, or printed, into surfaces (Underwood 2000, 136). Gutenberg’s press is predated by Chinese developments in hand-printable woodblocks (Stewart 2013, 254). Mechanical printing in the early modern period has been presented as a significant medium, as Elizabeth L. Eisenstein (2005, 14) writes “unknown anywhere in Europe before the mid-fifteenth century, printers’ workshops would be found in every important municipal center by 1500”. The workings of the world, and specifically the body, were theorised, investigated, recorded and printed as texts and images.

Printed early modern midwifery texts often detailed diverse areas including; anatomical descriptions of reproductive organs, cases of monstrous births and methods for determining the sex of a foetus. The generative ‘matrix’ converged with socio-cultural anxieties of gendered power relations, and specifically questions of how much each sex biologically contributed in producing offspring. While bodies were anatomically dissected through the early modern period, the processes of conception and the workings of the womb were still shrouded in mystery. For example, the anonymous author (1684, 25) of Aristotle’s Masterpiece writes that: “…nothing is more powerful than the imagination of the mother; for if she conceive in her mind, or do by chance fasten her eyes upon any Object, and imprint it in her Memory, the Child in its outward parts frequently has some representation thereof…”

Conceptually, the anonymous author is describing a process similar to printmaking—the matrix used to ‘imprint’ a similitude, and the author or maker is the mother. The excerpt is followed by the author’s suggestion that during sex a husband keep his wife’s eyes fastened on his face, and his face only, perhaps indicating an implied male readership. Within the text, female agency in reproduction is cast as something potentially powerful and consequently something that must be controlled and monitored within the marital bed. The shifting gendered power-relation, as conceptualised in the above quote, appears in tension with older philosophical voices. For example, Ancient Greek philosopher Aristotle employing humoral theory stated, “females are weaker and colder in nature, and we must look upon the female character as being a sort of natural deficiency” (Aristotle, translated by Jonathan Barnes 1958, 1199). Biblical, agricultural and craft-based metaphors were often drawn on to elucidate what seventeenth century authors considered to be the ‘secret’ interior workings of the female reproductive body to a broader society (Fissell 2003, Park 2010).

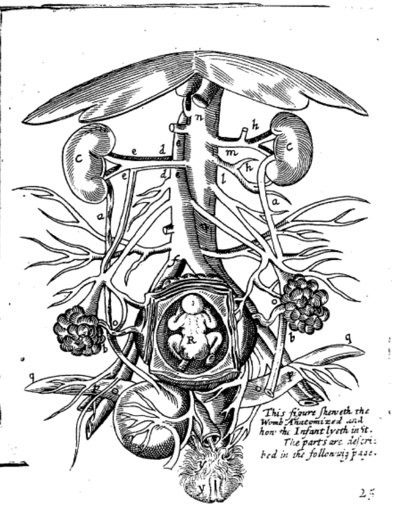

Figure 5: Anonymous, The English Midwife Enlarged, 1682,

Copy from John Rylands University Library of Manchester.

Accessed via Early English Books Online, National Library of Australia.

Textual and image-based representations of the womb in the seventeenth-century were highly symbolic. The female body was visually represented in midwifery texts predominately through two modes—the whole body, alive, and yet partially dissected open or as floating disembodied reproductive organs. Often hands were arranged to cover breasts and external genitalia. These prints were often repeated across editions and texts, for example Figure 1 from Thomas Chamberlayne’s The Complete Midwifes Practice published 1656, can also be found in Louise Bourgeois’s The Complete midwife’s Practice Enlarged published 1663, Hugh Chamberlen’s The Complete Midvvife’s Practice Enlarged in the most weighty and high concernments of the birth of man published 1680, and John Pechey’s The Complete Midvvife’s Practice Enlarged in the most weighty and high concernments of the birth of man published 1698. The prints of female bodies frequently included floral motifs, with flowers covering public hair and labia, petal like shapes forming opened abdominal regions and flower buds hand-held and partially hidden behind women’s bodies. Jonathan Sawday (1995, 226) suggests that within early modern anatomical texts, “metaphors acted not only to explain everyday function (or dysfunction) and structure but to constrain the body with the overarching organisation of patriarchal authority”. These printed lines offer a partial insight into seventeenth-century understandings of the female reproductive body. This insight is like a complex lens, which is coloured by early modern male physicians, anatomists and authors, it is sticky with the inheritance of older medical, philosophical writers, such as Hippocrates and Aristotle, and it is also rendered opaque through time to eyes of the contemporary researcher.

Sara Ahmed’s (2010) affective exploration of things which ‘stick’ is drawn upon as a methodological tool, in considering modes of ethically negotiating historical artefacts and considering texts that stay with me, seeping into my flesh. Here contemporary articulations, negotiations and analysis of language and image become political. The descriptor ‘naked’ is selected in response to Kenneth Clark’s (1956) text The Nude, which examines iterations of human, often female, nudes within art history. Clark’s discussion of various artistic representations of bodies in art, spanning ancient to modern times, centers on an identification of an aesthetic and ideological shift from ‘naked’ to ‘nude.’ Clark suggests western notions of ‘nakedness’ are associated with an almost raw, unshaped form because “we are immediately disturbed by wrinkles, pouches and other small imperfections which, in the classical scheme, are eliminated” (Clark 1956, 4). Clark identifies and pursues an impulse within western art discourses where naked human bodies are elevated to a representational, ‘nude’ state. This is a textual move which I seek to complicate through the use of my body. A body with hair, flesh that bulges in places, and changes as I age. This embodied position is grounded in ongoing feminist redress of the western art canon, marking sustained critique of gendered power relations with the gallery and broader art world (see for example the Guerrillagirls). Articulations of bodies, through text and images, carry symbolic meaning. The seventeenth century print, from Thomas Chamberlayne’s text, shifts between an anatomical model-based representation of the female body, while also containing symbolic details which potentially allude to broader social-cultural factors. This image, like the lived body, is complex, refusing singular analysis.

Figure 6: Wandering Womb, stop motion video, lino prints on the body of the artist.

Gallery 1, Trocadero Art Space, 2018.

Image credit: Matto Lucas

Methods of recording and presenting knowledge and beliefs about the human body, and specifically the female reproductive body, can maintain or challenge overt and underlying sociocultural power structures. This is not a linear or definitive process, but instead occurs through time and interconnected webs of actions. In Wandering Womb, a stop motion video, my naked body is progressively layered with a skin of cellular transparent lino prints. From my pubic hair prints appear to grow up and down my torso until my whole body is covered; a coating-skin-armour layer. The wet, slippery paper prints appear as deep blues, reds and purples that swirl and swell across my flesh. Traces of skin remain visible through the transparent prints.

Seventeenth-century visual representations of the female reproductive body are silent, they are printed and embedded into the pages of anatomical and midwifery texts. It is unclear whether these representations were translated from life, from anatomised corpses or from other drawings. These printed women are anonymous. Akin to the anatomised textual female bodies, there is a tension in my video artwork, an uneasy feeling that my naked body is presented to be looked at or objectified. However, as my body becomes a blue and red cellular relief print form, my gaze looks down at its own flesh, acknowledging this transformation and then looks out to meet the eyes of the viewer. Comparatively, the gaze of the afore discussed historical female printed body is downturned, permanently cast and printed in an unequal gendered power relation. The returned gaze in the video artwork, Wandering Womb, unsettles a traditional gendered relation of looking. Furthermore, the silence in the video work acts as a provocation to the viewer. This process of looking back, acknowledges the silence of seventeenth century representations of women’s bodies, and becomes a powerful reminder to a contemporary viewer of the lineage and spaces of patriarchal societal structures.

Conclusion

To conclude, while female reproductive bodies persist as sites of contestation, re-evaluation and creative re-printing within my work of historical bodily notions in the present opens potential for critical reflection. This can lead to an awareness of persistent modes of representation and their impact on broader socio-cultural understandings of female bodies. This article does not offer conclusive or definitive answers, it does however, through specific examples from the early modern period and contemporary discourses, reveal sticky affective gendered bodily understandings. Working diffractively, reading diverse authors, disciplines, and multiplex research practices together, with and through the body offers spaces where reflexivity and positioning within writing and making can be engaged and clarified. As discussed within this article, representations and ‘histories’ of the body are constructed; these constructions are active and ongoing however representations of the body can be short circuited, revised, re-told, re-printed, re-visioned and voiced through difference.

Works Cited

Ahmed, Sara. 2010. Happy Objects In The Affect Theory Reader. Edited by Melissa Gregg and Gregory J. Seigworth. Durham: Duke University Press.

Ammer, Christine, and Joann E. Manson. 2009. Encyclopaedia of Women’s Health. New York: Infobase Publishing.

Anonymous. 1684. Aristotle’s Master-piece. London: Printed for J. How. Early English Books Online, National Library of Australia.

Arikha, Noga. 2007. Passions and Tempers: A History of the Humours. New York: Harper Perennial.

Aristotle. 1958. Complete Works of Aristotle Volume 1: The Revised Oxford Translation. Translated by Jonathan Barnes. UK: Princeton and Bollingen.

Baird, Barbra. 1998. The self-aborting woman. Australian Feminist Studies.13(28): 323-337.

Barad, Karen. 2007. Meeting the Universe Halfway. Durham: Duke University Press

Boursier, Louise Bourgeios. 1698. The Complete Midwife’s Practice Enlarged… London: printed for H. Rhodes. Early English Books Online, National Library of Australia.

Bryant, Lia. 2016. Critical and Creative Research Methodologies in Social Work. United Kingdom: Routledge.

Burgess, Georgie and Tamara Glumac. 2018. Tasmania’s only abortion clinic closes, putting pressure on government to find alternative. ABC.net.au. Viewed 5 February 2019. < https://www.abc.net.au/news/2018-01-13/tasmanias-only-abortion-clinic-closes/9325194>

Chamberlain, Walter. 1972. The Thames and Hudson Manual of Etching and Engraving. London: Thames and Hudson.

Clark, Kenneth. 1956. The Nude. Harmondsworth, UK: Penguin.

Crawford, Patricia. 2014. Blood, Bodies and Families in Early Modern England. Abingdon, Oxon: Routledge.

Darroch, Gordon. 2017. Dutch respond to Trump’s ‘gag rule’ with international safe abortion fund. thegaurdian.com. Viewed 5 February 2019. < https://www.theguardian.com/global-development/2017/jan/25/netherlands-trump-gag-rule-international-safe-abortion-fund>

Eisenstein, Elizabeth L. 2005. The Printing Revolution in Early Modern Europe. Cambridge; New York: Cambridge University Press.

Ellis, Carolyn, Adams, Tony E. Bochner, Arthur P. 2010. Autoethnography: An Overview. Forum: Qualitative Social Research Sozialforschung. 12 (1): n.p.

Fissell, Mary E. 2003. Hairy Women and Naked Truths: Gender and the Politics of Knowledge in “Aristotle’s Masterpiece”. The William and Mary Quarterly. 60 (1): 43-74.

Fissell, Mary E. 2004. Vernacular Bodies: The Politics of Reproduction in Early Modern England. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Gowing, Laura. 2012. Gender Relations in Early Modern England. Harlow, UK: Pearson.

Greg, Mellissa & Gregory J. Seigworth. 2010. The Affect Theory Reader. Durham N.C.: Duke University Press.

Haraway, Donna J. 1997. The Virtual Speculum in the New World Order. Feminist Review. 55 (1): 22-72.

Hobby, Elaine. 2001. “Secrets of the female sex”: Jane Sharp, the reproductive female body, and the early modern midwifery manuals. Women’s Writing. 8(2): 201-212.

Juelskjaer, Malou and Nete Schwennesen. 2012. Intra-active Entanglements – An Interview with Karen Barad. Kvinder, Koen Og Forskning. 21 (1-2): 10-23.

Kalof, Linda and William Bynum. 2010. A Cultural History of the Human Body in the Renaissance. Oxford: Berg.

Levy, Michelle and Tom Mole. 2017. The Broadview Introduction to Book History. Ontaria: Broadview Press.

No author. 2019. Offences Against The Person Act 1861. Legislation.gov.uk. Viewed 27 May 2019. <https://www.legislation.gov.uk/ukpga/Vict/24-25/100/crossheading/attempts-to-procure-abortion>

Oxford English Dictionary. n.d. Womb, n. Viewed 27 May 2019. <http://www.oed.com/view/Entry/229912?rskey=nIkbis&result=1&isAdvanced=false#contentWrapper>

Park, Katherine. 2010. Secrets of Women: Gender, Generation and the Origins of Human Dissection. Cambridge, Massachusetts: Zone Books

Porter, Roy. 2003. Flesh in the Age of Reason: The Modern Foundations of the Body and Soul. New York: Norton.

Sawday, Jonathan. 1995. The Body Emblazoned: Dissection and the Human Body in Renaissance Culture. New York: Routledge.

Sharp, Jane. 1999. The Midwives Book, or the Whole Art of Midwifry Discovered. Edited by Elaine Hobby. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Stewart, Alison G. 2013. The Birth of Mass Media: Printmaking in Early Modern Europe. In A Companion to Renaissance and Baroque Art. Chichester: John Wiley & Sons.

Underwood, Will. 2000. On Presses and Press Marks. Journal of Scholarly Publishing. 31 (3) (04): 136.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivs 3.0 Australia License.

ISSN: 2202-2546

© Copyright 2015 La Trobe University. All rights reserved.

CRICOS Provider Code: VIC 00115M, NSW 02218K