Section 1

Xenokin and Queer Morphologies

Virginia Barratt, Francesca da Rimini, Alice Nilsson

Abstract

Xenokin and queer morphologies is a text for three voices, presented as a performed lecture at the 2018 Gender, Sex and Sexualities conference in Adelaide. The proposals herein are situated on the borderlands of the empirical/speculative and engage with notions of “xenofam” (Hester 2018, 65) and, following Haraway, queer morphologies. We materialise the speculative as we “build” and “create” home and family outside of the white, cis-het, patriarchal genetic-social order, using the poetic as a mode of reportage.

The performing voices—WitchMum, Mum 2.0, code child/precocious meme savant—have cooked, co-habited and coded as becoming-kin to instantiate xenofam, building affective bonds through which datablood flows. This queered approach to extensible and open family platforms generates intentional spaces for the reconfiguration of blood ties beyond blood types, and, hyperstitionally, another mode of hexing Capital.

Keywords

experimental writing; feminism; xenofeminism; queer kinship; autoethnography

FULL TEXT

Invocation #1

Voice 1

‘Etymologically, XENO is trans. It is the foreign and the foreigner, the unexpected outside, the unlike offspring, the other within, the eruption of another meaning. XENO is of its own order. It is a foreign agent, speaking its own tongue, keyed to its own purposes’ (Sheldon 2017).

Voice 2

‘Capitalism so deeply threatens the reproduction of our life that our revolt against it cannot be tamed’ (Mies & Federici 2014, xii).

Voice 3

‘As capitalism slides despotic civilization into collapse, the deterritorialized familialism nucleated upon Oedipus becomes the principal agent of social reproduction’ (Land 2012, 428).

Voice 1

We are experimenting with creating xenokin, mostly in meatspace, which has been compelling enough to engage us in its materiality, through domestic and social practices. We use some terms interchangeably, as we consider that terminology is a dynamic force, a becoming, and that all terms are partial, provisional and often apparently contradictory.

fam/family/familiars are deployed in various states of critique and contradiction.

kin/kind are variously applied.

they is used in the singular as a pronoun, to indicate non-binary or agendered persons.

We are casting a typology of the xenofamiliar, its ingredients still in flux as the cauldron approaches the hob.

Voice 2

We are committed to praxis, that is, the practical application of a theory through iterative processes of action/reflection, a concept that has been central to the critical literacy and conscientization work of Paulo Freire (1996) and others associated with the radical pedagogy movement emerging in the early 1970s in South America. These praxes, interrogating and pushing back against colonialist and capitalist modes of exploitation, are rooted in earlier traditions, such as Autonomia Operaio in Italy, bringing to life Marxist activist philosopher Antonio Gramsci’s notion of the ‘organic intellectual’ and new social formations of workers/philosophers in factories and poor peripheral zones in post-war Italy (Gramsci 1992, 1).

This type of approach, of interrogating one’s individual and collective lived experiences to identify and fight against modes of oppression, has been a touchstone for feminist work for centuries. We find examples in the work of Mary Wollestonecraft (Wollstonecraft 2002) A Vindication of the Rights of Woman (first published in 1792), the Wages for Housework campaigns of the 70s (Federici 1975), the inspiring Comandanta Ramona of the Zapatista movement in Mexico (Rabasa 2006), and Patrisse Cullors, one of the progenitors of Black Lives Matter (Khan-Cullors 2016). Like them, countless feminists and accomplices have interrogated the prime causes of oppression, and suggested or led pathways out of the patriarchal capitalist mire.

Voice 3

Our project can be seen as an act of speculative fiction, a hyperstition (Carstens 2009). Our familial fiction becomes real with repeated incantations of “the kid”, “witch mum” + “mum(2.0)”. It goes from a virtual differentiating to an actual differenciating (Boundas 2006, 397-423).

Voice 1

xenofam avatar: Mum2.0

pronouns: she/they

what: queer stranger, walking dead, panic merchant

mode: shimmer body

Voice 2

xenofam avatar: WitchMum

pronouns: undisclosed

what: ghost doll/oracle snatch becoming crone doll/closet queer

mode: Hexological

Voice 3

xenofem avatar: codechild/witchchild

pronouns: she/they

what: precocious meme savant, affirmative annihilation force, synth-pop fiend

mode: Left-Hand Path

Voice 1

What are we to one another? We live separately and together. WitchMum and Mum2.0 are a non-sexual assemblage of a larger assemblage, or what Lyn Margulis might call a ‘holobiont’ (Margulis 1991, 2), in its micro and macro aspects.

Together and separately we practise the creation of “home” through parenting/mentoring/witchery/domestic and emotional support/daily affective labour and the labour of care. We do this for each other and for others strangely attracted to this arrangement. Through these practices we provide a haven from, or extension to, the nuclear family unit, for outliers on the brink of that system. We are open-platforming “family”.

Voice 2

codechild/witchchild became entangled in our heretical experiment, and we in theirs, a mutual entanglement that is sympoietic, an open system of generative kinning. We each come to this particular arrangement with our attendant sprawling networks of connectivity. The “mums” did not (bio)produce the child, rather we are co-creating becoming-kin, we all birthed one another.

Voice 3

As deviant subjects we are family-hostile, if (the nuclear) family is to be taken as the building block of a (hetero- and homo-normative) patriarchal late-capitalist state, as a unit reproducing a white, cis-het, patriarchal genetic-social order. Or if stepping outside this basic unit makes us uncivilised.

Voice 1

In one way or another, this configuration of relations is deviant to the dominant paradigms, because it is non-reproductive, non-binary, because it queers time and genealogy and allows for intervention and interruption, because it explodes into a web of sticky bonds that unfurl without limit, welcomes the stranger (and the “strange”), and does not recognise bloodlines as a delimiting factor in determining kin. It potentially allows for a radical reinterpretation of family and kinship.

Voice 2

If, as Shulamith Firestone (1970, 212) suggests, “family” is too much associated with systemic violence to be repatriated as a concept, is the same true for the concept of “kinship”? These are provocations to drive the experiment forward.

Voice 3

These ideas of kin (and, extensively, “kind”) are an integral part of this political project of, to use Hester’s (2018, 66) term, ‘defamiliarization’. Similarly, in Staying with the Trouble, Haraway (2016, 93) suggests a slogan for the boundary event she calls the Chthulucene: ‘Make Kin Not Babies’.

Voice 2

“Making kind” is a different order of gathering together non-genetic non-species likeness, and also most beautifully extends kin to imply kindness.

The wild law and earth jurisprudence movements explore what “kind” might entail, in efforts to redress the destructive anthropocentrism that existing legal and political structures are based on. For example, Te Awa Tupua in Aotearoa has been granted human rights as an ancestor river (Te Awa Tupua Act, 2017). Of the river, their family begins with the view ‘that it is a living being, and then [we] consider its future from that central belief’ (Moylan 2017).

Voice 1

The prefix “xeno” comes from the Greek word “xenos”, meaning the stranger, the outsider, or the alien.

Rebekah Sheldon, a researcher into the queer occult, identifies “Xeno” (2017) as method: its qualities of strangerness, being open to the “outside”, to the wholly unknowable, makes it a perfect site for experimentation. In this case, the site of family is our experiment, the practice of “xeno-kinning” a work of productive resistance to the capitalist unit of the nuclear family.

We find the prefix xeno- also mobilised by the collective Laboria Cuboniks (2015) who authored the virally disseminated Xenofeminism: A Politics for Alienation.

Figure 1: Screengrab from the online version of Laboria Cubonik’s Xenofeminist Manifesto

Voice 3

Laboria Cuboniks member Helen Hester contends that Xenofam praxis contributes to the feminist multiverse. It aims to ‘create the conditions whereby the [biological] family stops being the centre of the way we conceive of what’s possible for social reproduction … by creating cultural spaces for alternatives’ (Barry 2018).

Voice 2

This enormous task challenges how societies are structured and people subjugated via toxic combinations of Capitalism, Statism, fundamentalisms, racism, colonialism, classism, and so forth.

This project must not remain in the speculative realm. It demands collective practical experimentation to ‘disrupt the idea that there are correct and incorrect ways of being a socially reproductive unit’ (Barry 2018). Once disrupted, emergent forms can arise.

Figure 2: Homocult poster, from Queers with Class

Voice 1

There is not an instant I can identify as the instant we switched from people who knew each other to becoming-kin. Maybe we haven’t reached the instant and of course we never will, since we are perpetually approaching it, peering towards a horizon that is shrouded in illusory fogs.

There is not a day I can celebrate as the day we become more than we already were to each other. More strange and more familiar, both.

There is not a day I can mark as the day we gave birth to each other—witches and queers, avatars and heretics—a performative birthing from parts unknown, an ectopod made of paper, string and texts and the dry electricity of the street. Rain, a fractured score, feet on floorboards, climbing stairs. Or maybe a sweaty day in 1990 before we were born. A spelling of ambience, affect and time.

It’s not just who she is to us or what we are to her, but who we are to one another, in fluid relationship to all the other others—strangers sensing frequencies of affinity and taking risks, inventing endearments, becoming sticky, sharing food, turning down beds, mopping up tears, leaning in, trusting, learning the edges, taking care.

It’s not that our nets are not already brimming with love and loves, but we cannot stop the webs from spinning themselves.

Invocation #2

Voice 3

‘Desire is never separable from complex assemblages. Desire is never an undifferentiated instinctual energy, but itself results from a highly developed, engineered setup rich in interactions’ (Deleuze and Guattari 2005, 215).

Voice 1

‘It is productive to think about utopia as flux, a temporal disorganization, as a moment when the here and the now is transcended by a then and a there that could be and indeed should be’ (Muñoz 2009).

Voice 2

‘Will we be strong and numerous enough in the coming insurrection to create rhythms that prevent apparatuses from forming again, from assimilating that which in fact happens?’ (Tiqqun 2011, 204).

Voice 2

As we are building xenofam, connecting over cooking, coding, coddling, talking over tables, texts, and emails with no subject lines, we are simultaneously creating the conditions for experiences of loss and nostalgia.

Conditions feeding hrepenenje—that Slovenian concept Marko Peljhan told us long ago in St Petersburg. No match for it in English, yearning perhaps a distant cousin, but maybe not. Hrepenenje, a sweet melancholy. A pain to be savoured, treasured, not least because it reminds us that we are alive.

Already I am thinking 6 months ahead when the child, our precious meme savant, our beloved and be-lived, will be gone, moved away, to a city grimier and queer tribier.

A city more melodic and episodic, holding more opportunities for sex and breath and impossibly cute girls to crush on. A place from which to burst from chrysalid to Spilosoma lubricipeda, white ermine moth, in all its horned and spotted splendour.

Figure 3: Spilosoma lubricipeda

Too sad.

But too early for hrepenenje.

Because she’s not yet gone, she’s still in her room of books and aluminium vials. All that cream she must be whipping, all those fun fountains of youth.

I miss her.

So I play Massive Attack to rub sand into my wound.

‘I’m a boy and you’re a girl.’

A-bonding has within it abandon, a band made of rubber, stretches out, pings back, snapping at our wrists like a miniature terrier on night patrol.

‘I’m here. I’m here.’

Keeping it fey with WitchMum.

Keeping it real with Mum2.0.

Keep us with you in your phantasmagoric Nang tent,

through 60 tiny explosions of momentary bliss,

faster than a speeding meme.

Already I’m thinking of who might be good to step into our xenofam shoes, accomplices of her own gen she has now, but a murder of crows in melbz might be useful too.

Perhaps a cohort of small crones, or a small cohort of crones.

Whatever it might be, the shape and flow of her extended xenofam elsewhere, we shall haunt her, far-sight her, telepath when we wake.

Voice 1

Recently a friend presented me with an important provocation, highlighting the privilege required to research in this area, and to casually apply concepts which have a deep history of causing harm.

‘How is this (xenofam) distinct from queer kinship? And is kinship too saturated with nationalism for westerners to be trusted with it as an infrastructure for building new worlds?’ (redtremmel, 2018).

Voice 3

While I am reluctant to abandon queered family (which is not the same as queer family), I take as a starting point Firestone’s position that the family is the seat of systemic violence, especially in terms of constructing normative hegemonies and, consequently, deviant subjects within a punitive system (Firestone 1970).

Figure 4: ‘Family’. Found image.

I feel that family as a concept is too saturated with trauma histories to repatriate it. Kinship might also suffer from that same saturation, but we take heart from the work of David Eng (2010) who contemplates ‘the collective, communal, and consensual affiliations as well as the psychic, affective, and visceral bond[s]’ (2010, 2) of kinship; Janet Carsten’s (2004) work to explore how gender, personhood, code, substance and the house are constitutive of kinship; and the work of queer ethnographer Kath Weston (1991, 29) who proposes that the queer kinship model exists outside of the linear heteronormative progression of time. Not to mention, of course, Haraway’s work to extend kinship to the more-than-human.

Voice 1

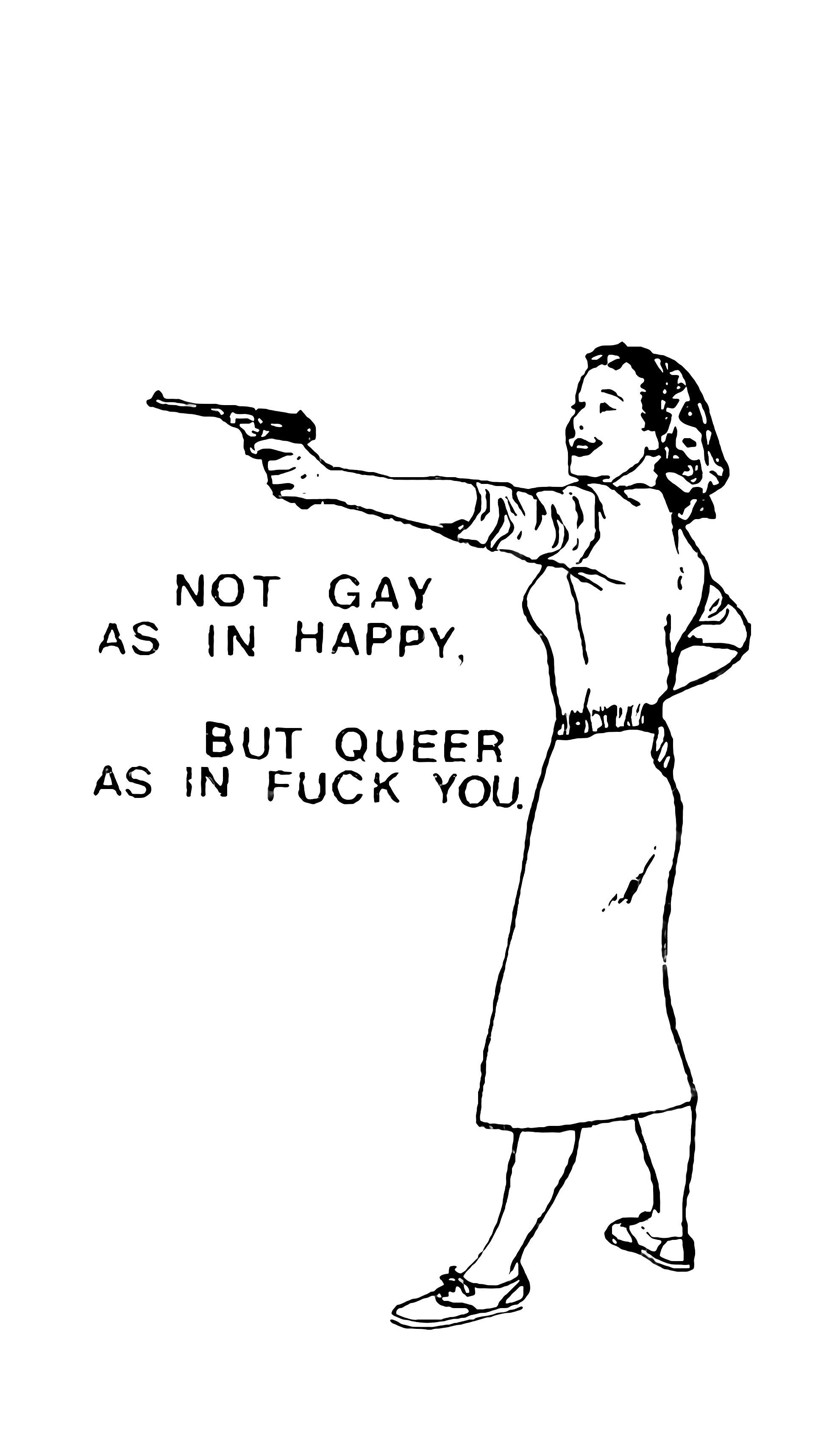

I’ll gesture here towards what David Eng (Eng 2010, xi) calls ‘queer liberalism’, and what Enoch Mailangi, a Polynesian and Indigenous nonbinary creator from Western Sydney, would call ‘the optics of queer’ by suggesting that “queer” has become depoliticised across time, unmoored from its roots as a reclamation of outsider status that Queer Nation rallied around in the late 80s. The slogan “not gay as in happy, but queer as in fuck you!” which was a product of that time is greeted with disapproval in these times where a liberal human rights version of queer strives for acceptance. So queering as method has been thrown under the bus for queer as acceptable identity.

Figure 5: Queer Nation slogan, origin of quote and image unknown.

Also used by Agatha in their 2009 song ‘Queer as in Fuck You’

I propose that Xeno, in Sheldon’s version, is a methodology along which lines strangers can become “familiars” or kin(d) through a process of defamiliarization, by becoming strangers to ourselves. As Sheldon says, xeno ‘presumes that the force of the other is always wholly other’ (Sheldon 2017). There is a darkness to Sheldon’s Xeno, but it is a welcome darkness, implying ‘a horizon of action that cannot be determined at the outset’ (Sheldon 2017). There is no predetermination in Xeno-kinning.

Voice 3

Xeno + queering both align with Deleuze’s writings on difference (or becoming) which have at their core an ontological presupposition that everything is in a constant state of change, nothing is ever static or finished, but is in a constant state of becoming (Boundas 2006). This is counterposed to other philosophies that Deleuze identifies as being concerned with identity and unity. This is not to say that identity is not important, but these philosophies saw identity as a static state. One was always black, one was always white, one was always man, one was always woman. These philosophies relegate subjects into segregated groups with no complexity or change (Rajchman 2001). Rather, for Deleuze, one is always between these states, moving towards one but never reaching it. There is nothing common here, just the constancy of striving to attain.

Voice 2

So what resources do we have at hand and how does xenokin coalesce? In this instance, the “we” is the xeno-family core of Mum2.0, witchchild, WitchMum.

Beyond this leaking profane trinity, a triangular formation that mirrors the hetero-normative patriarchal family unit, are a myriad of other relations that we weave in and out of, entangle ourselves, slip and elide.

Previously sanctioned domestic processes have attained a critical affective resonance through practising with strangers. That is, the personal became political: sleeping near one another, treading lightly, calling out, supporting, financing, feeding, gossiping, living through seasons together, arguing, crying, position shifting, holding ground, yielding.

This is a rich culture to grow strange in, to reinvigorate kin(d).

Figure 6: ‘XenoFamily’. Image by Barratt, da Ramini, Nilsson, 2018.

Invocation #3

Voice 2

‘We are the children of arson and fire’ (Micic 2017, 9).

Voice 1

We are living ‘a pact to face the world together’ (The Invisible Committee 2014, 71).

Voice 3

No slaves no masters!

ERA Statement

Research background

This text was first presented at the 2018 South Australian Postgraduate and Early Career Researcher Gender, Sex, and Sexualities conference: ‘Space and Place: Conceptions of movement, belonging and boundaries’, and is a response to the themes of kinship and connection. The text is the result of an experiment in co-creation through the application of situated knowledges (Haraway 1988, 575-599). By turns autoethnographic, speculative, and poetic, the text responds affectively to the work of building ‘xenofam’ (Hester 2018, 65) and kin beyond ties of blood and genealogy.

Research contribution

The proposals herein are situated on the borderlands of the empirical/speculative and engage with notions of ‘xenofam’ (Hester 2018, 65) and, following Haraway, queer morphologies (Haraway 2003). The authors materialise the speculative as they “build” and “create” home and family outside of the white, cis-het, patriarchal genetic-social order, using the poetic as a mode of reportage. Much like two of the authors’ experiences in the cyberfeminist group VNS Matrix, the project attempts to build the future linguistically and affectively. This life-as-laboratory approach shares a resonance with queer theorist José Muñoz’s deployment of ‘doing in futurity’ (Muñoz 2009, 26)—that is, a concept of a queer politics that pivots away from the ‘ontologically static … here and now’ of the homonormative, and towards more performative strategies for becoming queerly utopian.

The performing voices – WitchMum, Mum 2.0, code child/precocious meme savant – have cooked, co-habited and coded as becoming-kin to instantiate xenofam, building affective bonds through which datablood flows. This queered approach to extensible and open family platforms generates intentional spaces for the reconfiguration of blood ties beyond blood types, and, hyperstitionally, another mode of hexing Capital.

Research significance

Xenokin and queer morphologies is a work of co-creation and situated research, contributing to the field of queer kinship studies through a lived experiment of building xenofam, taking Shulamith Firestone’s (1970) call to destroy the family unit at its word.

At the core of the work of these artist/researchers is their commitment to collaborative creative practices, and ongoing critique of notions of individual authorship proceeding from Barthes’ important work The Death of the Author (Barthes 1977) and more recent examples such as the DIWO (Do It With Others) praxis promoted by net art community Furtherfield (da Rimini 2010). As a text for performance, and for queering the academic paper, xenokin is an example of polyphony in univocity.

Works Cited

Barthes, Roland. 1977. ‘The Death of the Author’ in Image-Music-Text. Edited and Translated by Stephen Heath. London: Fontana Press. 142-148.

da Rimini, Francesca. 2010. ‘Socialised Technologies, Cultural Activism and the Production of Agency.’ Doctor of Philosophy in Humanities and Social Sciences thesis, University of Technology Sydney. 196-200.

Firestone, Shulamith. 1970. The Dialectic of Sex: The Case for Feminist Revolution. New York: Bantam Books.

Haraway, Donna. 1988. ‘Situated knowledges: The science question in feminism and the privilege of partial perspective.’ Feminist studies 14, no. 3: 575-599.

Haraway, Donna Jeanne. 2003. The companion species manifesto: Dogs, people, and significant otherness. Vol. 1. Chicago: Prickly Paradigm Press.

Muñoz, José Esteban. 2009. Cruising Utopia: The Then and There of Queer Futurity. New York: New York UP.

Bibliography

Barry, Robert. 2018. ‘Doing Gender: Helen Hester on Xenofeminism.’ The Quietus. Published electronically 31 March 2018 http://thequietus.com/articles/24298-xenofeminism-helen-hester-interview.

Boundas, Constantin V. 2006. ‘What Difference does Deleuze’s Difference make?’ In Deleuze and Philosophy. Edinburgh University Press. Edinburgh Scholarship Online, 2012. doi: 10.3366/edinburgh/9780748624799.003.0001.

Carsten, Janet. 2004. After Kinship. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Collective; Falling Wall Press. https://monoskop.org/images/2/23/Federici_Silvia_Wages_Against_Housework_1975.pdf

Cuboniks, L. 2015. ‘Xenofeminism: A Politics for Alienation.’ http://www.laboriacuboniks.net/.

Deleuze, Gilles, and Guattari, Felix. 2005. A Thousand Plateaus. Minneapolis: University of Minneapolis Press. 208-231

Eng, David L. 2010. The Feeling of Kinship. Durham and London: Duke University Press.

Federici, Silvia. 1975. Wages against Housework. Bristol: Power of Women.

Firestone, Shulamith. 1970. The Dialectic of Sex: The Case for Feminist Revolution. New York: Bantam Books.

Freire, Paulo. 1996. Pedagogy of the Oppressed. Translated by Myra Bergman Ramos. London: Penguin.

Gramsci, Antonio. 1992. ‘Problems of History and Culture’. In Selections from the Prison Notebooks. Edited and Translated by Quintin Hoare and Geoffrey Nowell Smith. New York: International Publishers. 1-23.

Haraway, Donna J. 2016. Staying with the Trouble: Making Kin in the Chthulucene. North Carolina: Duke University Press.

Hester, Helen. 2018. Xenofeminism. Cambridge: Polity Press.

Homocult. 1992. Queer With Class. Manchester: The Talking Lesbian. N.P.

Khan-Cullors, Patrisse. 2016. ‘We didn’t start a movement. We started a network.’

https://medium.com/@patrissemariecullorsbrignac/we-didn-t-start-a-movement-we-started-a-network-90f9b5717668

Land, Nick. 2012 ‘Meat (or How to Kill Oedipus In Cyberspace’ In Fanged Noumena: Collected Writings 1987-2007. edited by Robin Mackay and Ray Brassier. Falmouth and New York: Urbanomic and Sequence Press. 411-439.

Margulis, Lyn. 1991. ‘Symbiogenesis and Symbionticism’. In Symbiosis as a Source of Evolutionary Innovation: Speciation and Morphogenesis, edited by L. Margulis and R. Fester, 1-14. Boston: Massachusetts Institute of Technology.

Micic, Ljubomir. 2017. ‘Manifest Zenitizma (1921)’. Chap. 2 In Why Are We ‘Artists’? 100 World Art Manifestos, edited by Jessica Lack. London: Penguin. 7-15.

Mies, Maria, and Silvia Federici. 2014. Patriarchy and Accumulation on a World Scale: Women in the International Division of Labour. London: Zed Books.

Moylan, Brian. 2017. A River in New Zealand Now Has the Same Rights as a Living Human Being. Vice.com. Viewed 5 September 2018. https://www.vice.com/en_us/article/wnk4k4/a-river-in-new-zealand-now-has-the-same-rights-as-a-living-human-being

Rabasa, Magalí. 2006. ‘The Death of Comandanta Ramona’. Radio Zapatista, https://www.radiozapatista.org/ramona.htm.

Rajchman, John. 2001. ‘Introduction’ In Pure Immanence: Essays on a Life by Gilles Deleuze. New York: Zone Books 7-24.

Sheldon, Rebekah. 2017. XENO. theocculture.net. Viewed 5 September 2018. http://www.theocculture.net/xeno/

The Invisible Committee. 2014. To Our Friends (a Nos Amis). https://theanarchistlibrary.org/library/the-invisible-committe-to-our-friends.

Tiqqun. 2011. This Is Not a Program. Translated by Joshua David Jordan. Los Angeles: semiotext(e).

Weston, Kath. 1991. Families We Choose: Lesbians, Gays, Kinship. New York and Oxford: Columbia University Press.

Wollstonecraft, Mary. 2002 (1792). A Vindication of the Rights of Woman. Project Gutenberg, http://www.gutenberg.org/ebooks/3420

Khan-Cullors, Patrisse. 2016. ‘We didn’t start a movement. We started a network.’

https://medium.com/@patrissemariecullorsbrignac/we-didn-t-start-a-movement-we-started-a-network-90f9b5717668

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivs 3.0 Australia License.

ISSN: 2202-2546

© Copyright 2015 La Trobe University. All rights reserved.

CRICOS Provider Code: VIC 00115M, NSW 02218K