Section 3

When my body spoke out of turn

Cee Frances Devlin

Abstract

In the realm of traditional phenomenology, Husserl (via Ahmed) would point toward the table as (traditionally speaking) the background space “from” which philosophy is thought and written, a space of sacred (and usually undisturbed) contemplation (Ahmed 2006, 4). I would like instead to affirm Sara Ahmed’s (2006, 4) take in Queer Phenomenology on the table(s) at which we meet, a revival of this philosophically conceived furniture in its radical potential. Ahmed’s reading explains that our orientation towards such objects is directed and redirected by the level of ease with which we move through the world (2006, 4). Most of us, particularly those who occupy marginalised identities that carry trauma, are not afforded the uninhibited space to write our bodies into thought. In this instance, however, you are my captive (captured) audience, and so: I proceed by positioning the table as an evolving vessel between you, reader; and me, queer/trans/subject/author; a vessel that holds the power to make stories like the ones I have to tell audible.

Keywords

Gender; Violence; Trauma; Ahmed, Sara; Marginalised Identities

Full text

I’m going to tell you a story. A story that is not theoretical or sealed or written in my tongue—it is carried in baggage I cannot simply pass over. I am asking you to sit with me at this table and listen.

In the realm of traditional phenomenology, Husserl (via Ahmed) would point toward the table as (traditionally speaking) the background space “from” which philosophy is thought and written, a space of sacred (and usually undisturbed) contemplation (Ahmed 2006, 4). I would like instead to affirm Sara Ahmed’s (2006, 4) take in Queer Phenomenology on the table(s) at which we meet, a revival of this philosophically conceived furniture in its radical potential. Ahmed’s reading explains that our orientation towards such objects is directed and redirected by the level of ease with which we move through the world (2006, 4). Most of us, particularly those who occupy marginalised identities that carry trauma, are not afforded the uninhibited space to write our bodies into thought. In this instance, however, you are my captive (captured) audience, and so: I proceed by positioning the table as an evolving vessel between you, reader; and me, queer/trans/subject/author; a vessel that holds the power to make stories like the ones I have to tell audible.

Ahmed’s 2006 critique of the writing desk uncovers a renewed potential for traumatised bodies to speak and to tangibly “queer” their surrounds, both because we can (we are) and because there is no easy way to shirk the burdens members of our LGBTQIA+ communities carry. The discussion of tables and what they might represent (what they are already doing in our political and social spaces) can thus serve as a lived point of political contention and textual development in the bodies of work we build (together/apart). In this way, a table might become a new sort of meeting place or moment of possibility that we collectively push into view.

This table-tale is connected to so many others my body sustains, moments that flicker in and out of gaining “narrative” status (Halley 2008, 18) – mostly they move through andout again, too heavy to hold on my tongue or in my hands or in my walk. Halley (2008) uses the concept of “flickering” as a way to describe how (as writers and academics) we might move in and out of our alliances to particular theories. Though she is concerned with loosening a monogamous drive towards feminist theory, I also find the notion of “flickering” useful for describing how authorship and subjectivity within text is both hidden and revealed at different times and according to different motivating factors. So many of my body stories are disqualifying. They do not allow me to exist as I am in most spaces. My body’s stories reek – they give the tale away before I can tell it. The stories move, add and subtract (this is my memory now) and so, more than once I have spoken of the wrong testimonies at the wrong tables (Ahmed 2010, 2).

In Cathy Caruth’s cornerstone feminist trauma theory text Trauma: Explorations in Memory, Shoshana Felman asks if “the process of the testimony – that of bearing witness to a crisis or a trauma – [can] be made use of in the classroom situation?” (1995, 13). In my 2017 thesis, “Under the Table: Re/Writing the Trauma Fragment”, I posed my formulation of the table and its political relevance to the trauma survivor, a space where we may do what many traumatised bodies often feel is impossible: to bear witness for the witness (Celan 1980 n.p quoted in Eades 2017, 123). This work has been both a discursive investigation and a re-structuring of learning space: neat rows of forward-facing classroom desks are not the end game. The furniture involved in cracking open a trauma narrative is decidedly more complicated in configuration, and so in setting my own scene I have carefully considered the task of depicting a year of words in a life of wounds, work and writing, as well as the spaces through which they were mediated.

It is for these reasons that while choosing how to present my work I asked myself: what if I were to begin with the intention of complicating the trauma testimony? If I asked you to bear witness for the witness (this body, my body) breaking through the sticky shield of memory in protective gridlock via the “moment” of unexpected retraumatisation? After all, if ink had flowed from my fingers the first time my body was raped, who would have read my words? Would I believe them now? The traumatised body in revolt has reinscribed me (writing-body, activist ink) often before I was ready for its brutal honesty—propelling me beyond sterilised “victimhood” where the “I” exceeds (but does not succeed) in naming itself. The tendency for trauma to repeatedly (and haphazardly) name itself is not a discrete action/reaction relationship but instead a rearranging of the body’s impulses into scattershot formation. The effects often require the subject to remain at a certain level of un-knowing, unravelling linear timelines by blurring the lines between current and past realities (Caruth 1995).

I have already told you that this story involves furniture. I had read about Ahmed (2006) and her tables before I split my body open on their edges with a new meaning: before I looked up at one particular table from below and decided to touch both hands to the text of its underside.

If you Google my dead name, you will find versions of the story I am going to tell. What does it mean for a trans survivor to kill (in) their own name? I will always find solace in the bent up, folk-punk lyrics of June Jones:

“Trauma can live as a silent beast

Mine avoided naming for seven years

And on my very being it did feast

But I’ll starve the beast to death/

I was called a teenage boy

But I’d named myself a girl

You tore me up, buttercup

I was a threat to your whole world”

(Jones 2016).

Jones’s (2016) approach to song writing is as mischievous as it is devastating—a knack for grinding popularised verse through her own trauma recollections gives these stories breath in unfamiliar places.

If you type my “old” name (dead or otherwise, for me it will remain an in-between) into your search bar you will click and scroll and find arguments, discussions, and tired outrage. You will find journalistic angles with bodies flattened out or made absent. There will be comments about my body (my emotions; for they become one and the same), questions about my judgment, about why “sensitive” people bother to speak, or study, or work, or leave their houses at all. You will discover words like “thank you” and “you are so brave”. These relics do not sit comfortably when swallowed; my guts are not filled with a warm spreading sense of duty or good. By publicly cracking the illusion of occupying a liveable body (Butler 2009) I left it stuck in permanent, humiliating revolt: open and broken and speaking. I can never gather it back in the same tightly wound-around-wound, cocooned stasis that comes with the lived denial of the queer trauma wound (Eades 2017, 118).

Dear reader, I know you do not understand. I should tell you what happened in a way that will make this narrative more legible to your eye/ear. The trouble is, I have become far too familiar with repetition, and a prolonged exposure to hole-seeking missions in my tired testimonies has made choosing words no easy matter. It has also made me more inclined to misbehave when asked to report: again. Still, I must attempt to presentsome key facts of this story; though I cringe and curl away from keyboard, paper, lectern, and am forced to resent my own tongue.

I went to an event at Melbourne Comedy Festival in 2015. I was (finally) confidently queer and deeply feminist but I was okay with it, this social venture. I was okay with going along and drinking beer and listening to rookies try their hand at making me laugh. I needed a laugh. I travelled in a sizeable group: people I liked and didn’t. I sat in rows of chairs positioned too close to each other so that when I squirmed in my seat (foot cramped one leg scrambling with feigned ease to fold itself over the other) I would kick the chair in front, wait for heads to turn, wonder if I had incited irritation this time. I had to climb bodies and crossed legs to reach the bar, return again, refold my body, listen, maybe chuckle, but mostly: sip beer.

“You know it was a good date if you wake up with a fistful of hair and a shovel.”

This was the first joke (that night) that landed at the base of my spine and sent a wave of tension up to my shoulders, the base of my neck soaking drips of laughter from the crowd. I remember reminding myself that Iconsented to a level of banal violence by attending. At the end of the first half, I shift seats. I do not want to sit sandwiched between unknown men and plastic chairs. Instead, I decide to sit diagonal to the stage so that when the jokes misfire I can lean back and share gazes of boredom; eye roll disgust with women (I was “a woman” then; I have sat at that table, I will be required often to do so again, but that is another table-tango). The jokes are bad, and they seem to get worse. I retreat to the tiny outside area, where two men are smoking. They fall silent to stare. I awkwardly confess what I am escaping from. They continue to survey me blankly until I leave. I consider going home but I don’t want to miss the lesbian comic I like, so I stay. I behave.

The last act arrives onstage and he delivers an opening line on what “gays” and “black people” can joke about. Then he says the word “rapist,” casually aligning himself with the word, which is a joke of a joke that might return to assert its inherent (but yet unrevealed) cleverness, I suppose. Finally—we might have discovered a safe space to test the limits of looking like a rapist (or being one), while the crowd perches on the edge of what we will deign to laugh at and what will fall slack at our feet. I guess the performative social experiment of the comedy show could involve rape as the terribly witty edge of laughable reason, the proud defender of Free Speech ™ and the men who are most displaced by its limits. A fistful of hair and a shovel.

In any case, I hear the next lines of the comic’s act underwater because I am no longer sitting in my seat, I am underneath the table to the right of the stage, and I don’t quite know how I didn’t notice this silent spectacle of leaving. The chairs were quite high and it was a long way down, really, when I think about it. It was a long way down to sticky floor breathing heavily with heart kicking up against ribcage. I briefly considered clambering out awkwardly over the row of crossed legs (what about my jacket?) but it is hard to breathe and think so I sit still and suck in the confusion and relief of leaving in this way. I tune back in and realise the droning pitch of comedic monologue has stopped. The comic is asking a question of someone in the crowd (more gasps, we can do that here, cackle and gasp at what we shouldn’t). I feel a deep sense of pity for the target. It takes me one long minute to realise he is addressing me, the “girl under the table”.

I didn’t know then that this would become a naming that bent my body into a strange new shape. Like “Girl with a Pearl Earring” or “Girl with the Dragon Tattoo,” except I am unhiding, unhidden, undercooked, understood only through the object I have been assigned––the table I have slid beneath for cover has instead turned me outwards and placed my body in full view. I would like to imagine Ahmed joining me in this retrospective scene-setting, too, her words sinking beneath the skin of my hunched shoulders: “If authority assumes the right to turn a wish into a command, then willfulness is a diagnosis of the failure to comply with those whose authority is given…” (Ahmed 2015, 2, emphasis added).

How did he even see me? I say nothing. The comedian persists; he asks again what I am doing there. No, he doesn’t ask – he demands to know why I am there. There are many sets of eyes a crouching figure who is and is not me and I am stuck. The silence is unbearable and so I speak what comes, I say, “I don’t think rape jokes are funny” because that is the truth I, willful table-girl, have access to in that moment.

There are more words in a sequence hard to recall or I don’t want to do it for you straight. I will always be queering the testimony: blazing a path to meeting my own complex PTSD in a fragmented, urgent, impolite fashion. It serves my purpose to have you witness its messy affects.

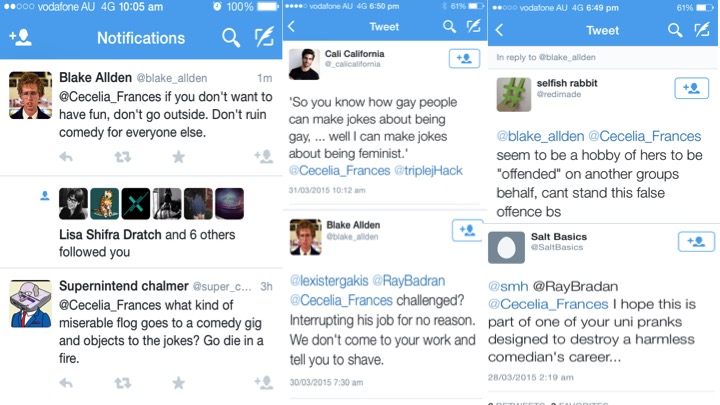

FIGURE 1: TWITTER COMMENTS 1

he Comic (Ray Badran):

“You probably shouldn’t ask someone who just called out a rape joke what their problem is, should you?”

“What is your fucking problem, though?”

“What is her problem?”

“You’re a piece of shit”

“Good on you for taking a stand”

“But—”

“You’ve ruined my night”

“This is the worst gig of my life”

The Public (Party for Ray):

“No I know him, and he’s a nice guy. Onya Ray”

“Fuck those negative bitches!”

“Boo! We’ll fucking fight you”

“Outside, now!”

The Twitter Feed:

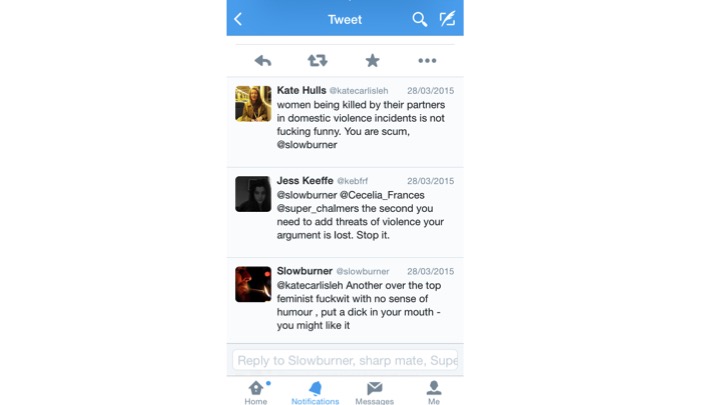

FIGURE 2: TWITTER COMMENTS 2

The comic, Ray Badran:

“Clap if you want me to keep going”

“You know what, good on you”

“But—”

“I hope you fucking die”

FIGURE 3: TWITTER COMMENTS 3

Testimonies rarely happen in a tidy, pre-planned fashion-–-and why would they? We are never assured that smoothing out our language, our academic work or our revolts will serve or save us, and the body (writing or otherwise) often has other ideas (Barthes 1973, 16). Barthes says, on the textual or writing-body: “The pleasure of the text is that moment when my body pursues its own ideas” (1973, 16), pointing toward the sprawling motivations of bodies who are simultaneously textual and active agents. He explains that we cannot separate writing from the lived body who is already making decisions about the stories we have to tell. In the Felman (1995, 13) chapter I referenced earlier, the author considers how the witness is not only pursued by, but pursues the interruptive quality of trauma affects through language, precisely by following the fragility and fragmentation of testimony itself (1995, 30). My hope is that stories like mine can be understood as “evidence” that our bodies and their interruptive moments can lead us beyond the surface (or table-top) of trauma retellings, and point us towards new narrative possibilities.

If we are to make space for the body that holds (but cannot contain, or conceal) trauma, then, we must consider the many drives to speak, the political potential that exists not prior to, but at all stages of trauma speaking, and the explosions of medium (rupture for rupture) we have at our disposal. Where does testimony become activism? What potentials for creative rupture can be found, hiding in plain sight, when our writing-speaking-bodies misbehave?

Works Cited

Ahmed, S. (2006). Queer Phenomenology In Orientations, Objects, Others. Place of Publication: Duke University Press.

Ahmed, S. (2010a). Feminist Killjoys (and Other Willful Subjects). The Scholar & Feminist Online 8(3): http://sfonline.barnard.edu/polyphonic/print_ahmed.htm

Ahmed, S. (2010b). The Promise of Happiness. Durham NC: Duke University Press.

Ahmed, S. (2015). Willful Subjects. Durham NC: Duke University Press.

Barthes, R. (1973). The Pleasure of the Text. New York: Hill and Wang,.

Caruth, C. (1995). Trauma: Explorations in Memory. Baltimore: John Hopkins University Press.

Eades, Q. (2017). Queer Wounds. In Talking Bodies: Perspectives on Embodiment, Gender, and Identity, edited by E. L. E. Rees, 118-130 , Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan..

Felman, S. (1995). Education and Crisis, or the Vicissitudes of Teaching. In Trauma: Explorations in Memory, edited by Cathy Caruth, page range. Baltimore: John Hopkins University Press.

Halley, J. (2006). Split Decisions: How and Why to Take a Break from Feminism.

New Jersey: Princeton University Press.

Jones, J. (2017). Decade of Disrepair . Two Steps on the Water. Viewed 20 June 2018.https://twostepsonthewater.bandcamp.com/track/decade-of-disrepair

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivs 3.0 Australia License.

ISSN: 2202-2546

© Copyright 2015 La Trobe University. All rights reserved.

CRICOS Provider Code: VIC 00115M, NSW 02218K