Article

Skating while black: Performances of race and gender within recreational ice hockey

Nikolas Dickerson

Abstract

In this paper I use auto-ethnography to illuminate how the sporting space of hockey can construct understandings of race and masculinity. Through personal vignettes I carve out the ways I am read as a black male within the space of hockey, while at the same time re-constructing my own identity as a black male through the writing process. Thus this paper uses evocative forms of writing to engage the reader and open up a dilagoue about the ways race and gender structure the space of sport.

Keywords

Gender; Race; Auto-Ethnography; Sport

Full text

Outside tiny white snowflakes glisten in the moonlight as they fall from the sky on a cold winter night in Iowa. Inside the white ice sparkles as an assortment of white hockey players go through their warm-up. The crowd of mostly white Iowans roars in anticipation of the upcoming game. I sit there with my long dreads and my light, bi-racial complexion and know without question that I stand out. I may look different but in a way I feel at home. Hockey has been my passion since I was twelve years old. Twenty years later I still get excited to step out on the ice for my weekly hockey game. I sit there enjoying the action on the ice until it happens. I am quickly reminded that I will always straddle the boundaries of inclusion and exclusion in my favorite sport.

I feel the hands in my dreads before the words come out. The woman behind me then says, “I like your hair, can I touch it”? I do not know how to respond to this question as her hand are already in my hair, so I just say, sure. I feel frustrated and uncomfortable as numerous thoughts race through my head.

Am I some sort of exotic pet that people haven’t seen before? What would have happened if I had placed my hands into the hair of the white woman sitting in front of me? If I say no, do I become the angry black man?

She tells me my hair is so beautiful it should be on display in a museum. Huh? I reply with an awkward thank you and turn back to the woman I am with who simply says: that just happened.

In many ways that story is synonymous with my experience playing the sport I love for the last twenty years. I am both an insider and outsider within the sport. More so, my experiences playing ice hockey are in many ways entwined with living life as a black male in the United States. The fascination and fondling of my hair is an experience I had many times during the eight years I spent in the Midwest. I often wonder what would cause another person to put their hands (especially without asking) into the hair of someone they do not know. But yet, I do know why some people feel the need to do so. For it is the same reason I have often felt and been treated like an outcast in my own country. Whiteness.

I have played hockey for the last two decades, and I struggle to come up with more than 15 names of racial minorities that I have played with or against. Despite the lack of other minorities playing the sport, I have loved this game since the day I started playing. The feel of the cold air against my face as I skate up and down the ice, the smell of dampness inside the arena, my skates and the rest of my body moving in unison, the speed of the game, and those moments when I contort my body in ways I didn’t think possible to make a desperation save: what is not to love? In fact, I have recently moved from the US to the UK and one of the first things I did was to join an ice hockey team. Perhaps more than any other position, as a goalie I am constantly in tune with my body. Yet while on the ice my body is often celebrated for its performance, as soon as I strip away the layers of protective equipment this same body becomes vulnerable.

In the remainder of this paper I use personal vignettes of my hockey playing experience to illuminate how the sporting space of hockey can construct understandings of race and masculinity. In this manner, my thoughts, politics, and emotions are at the center of this piece allowing the reader to interpret and make meaning of the stories I tell. Thus this text is meant to engage the reader by using evocative writing and allowing the reader to make sense of the ‘data’ as opposed to the author dictating how the reader should interpret the information on hand (Denison & Markula, 2003). Instead I offer questions for the reader to contemplate as they read this essay. How do power and privilege structure sporting spaces? How do people negotiate sporting space? How might we create safe sporting spaces?

These questions fit well with the autoethnographic approach taken in this essay. This form of writing offers a different way to understand the social world. Laurel Richardson (2000) argues that traditional forms of academic writing construct a limited space for knowing and telling, whereas autoethnography can open up new spaces for understanding our social world not visible in traditional forms of writing. It is the emotional component of this type of writing that is essential in opening up new ways of conceptualising our society.

Autoethnography helps engage readers, but also allows the researcher to decolonize their own mind by constructing their own identity, while drawing attention to how their identity has been conceptualized by others (Alexander, 2006). In other words, self-reflection allows the writer to draw attention to the ways their body is read by others. In this case, I am working through the ways I am read as a black male within the sport of hockey. At the same time, autoethnography allows the writer to construct a new narrative about their identity through the writing process (Alexander, 2006). Throughout this essay I go back and forth between how other hockey players have conceptualised my black male body and how I have understood my own gendered and racialised body. I conclude this essay by discussing where I have come in my own understandings of my identity and where I hope to go.

1. TO KNOW ME, YOU HAVE TO KNOW HOCKEY

I am a goalie. I do not get to deliver checks out on the ice, but I do get to use my body to stop a hard round rubber object from going into my net.

The satisfaction of watching a player hitting the puck as hard as they can and then using your body to deflect it away from the net is difficult to explain. It feels so good though.

Olympic hockey is my favorite type of hockey, because of the speed, the skill, and de-emphasis on fighting and the big hit due to the larger ice surface. Fighting and huge hits are at the bottom of the list of why I like hockey. There is one particular moment though where I cannot deny my appreciation of the big hit.

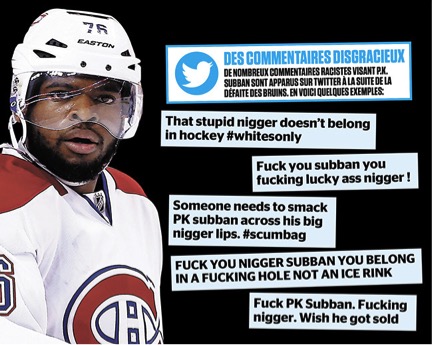

FIGURE ONE-COLLECTION OF TWEETS ABOUT PK SUBBAN

On December 16, 2010 the Montreal Canadiens played a game against the Boston Bruins. At the end of the first period of play, Afro Canadian player P.K. Subban of the Montreal Canadiens delivered a bone, hit to Brad Marchand of the Boston Bruins. (P.K. Subban almost killed Brad Marchand, 2010). I use this clip in class all the time. It is quite helpful in generating a discussion about gender, sport, and how we conceptualize what sport is. The hit in question was a legal, but Brad Marchand is a human being who could have been seriously hurt by the physicality of the blow. However, I know I get some satisfaction from watching that clip over and over. It’s Pk Subban against Boston. Boston, Boston, Boston (see Allen, Brady, & Hampson, 2012). Boston, a place where some of the worst race riots in US history took place.

A select number of Boston Bruins fans also made racist comments about another black player, Joel Ward in 2012 via Twitter. In response, Joel Ward stated, “It’s a few people that just made a couple of terrible comments, and what can you do? I know what I signed up for. I’m a black guy playing a predominantly white sport. It’s just going to come with the territory. I’d feel naive or foolish to think that it doesn’t exist. It’s a battle I think will always be there.” (Joel Ward, 2012) Unlike Joel Ward and PK Subban, my hockey-playing career has never come within site of the elite levels. Yet I share similar stories of being marked as the Other within the sport of hockey and in the world outside of sport.

To understand who I am, where I was, and where I am going, you have to know hockey

2. OH, I DIDN’T KNOW YOU WERE BLACK

I sit there highly focused on taping my stick. It is a few minutes before our game and I am lost in thought. My teammates are buzzing with noise as everyone is getting excited to get out on the ice. I am oblivious to the exact details of any specific conversation but suddenly my ears pick up on something I can’t ignore. “All black girls have names like Laquisha”. I can feel my face become flush and all I can do is look at the floor. I am not a young black girl, but I cannot help but feel that this comment about me, my blackness. Despite the large amount of hockey equipment that helps fill out my small 115-pound frame I feel like I am shrinking.

Doesn’t he know I’m black? Does he think I’m weird too?

I feel frozen in place as an awkward silence envelops the room when all of a sudden another teammate says, “Don’t you know Nik is black?” Given the string of apologies that follow, I do not know if this is a factor that has eluded my teammate or if he simply didn’t have any sense of the effects of his original remarks. Either way I just want this encounter to end and so, I accept his apology and try to concentrate on the game at hand. The quicker this moment ends the faster I can push it out of my mind.

What does it mean to be black? Am I not black enough? My dad is black, but I hate him. When can we get out on the ice? When can I use my body to fit in?

3. TAKING THE BODY

I am fourteen years old and even though I am short and skinny I have no problem with the physicality of ice hockey. I get an odd sense of satisfaction in my ability to take a big hit and get back up. Yet at the same time getting hit also provokes a sense of anxiety. Before every game I can’t shake the butterflies I have until I have taken that first hit. It is only then that I can move past the anxiety of the inevitable body to body collision. After this first moment of bodily contact, I remember that I can do this. My body can handle it. I am tough enough to play this physical sport. I am not afraid.

I know how to be masculine on the ice but not outside of the rink. On the ice I don’t have to feel and I don’t want to feel. Skate! Gotta get back on defense.

I feel the cold air hit my face as I skate from one end of the ice to the other. I reach our defensive blue-line and I pivot my wiry 130-pound body around to begin skating backwards. As I take my first backwards stride I see the puck-handler right in front of me.

He has his head down. Just put your shoulder right through his chest.

I close my eyes during that initial moment of impact and open them to see my opponent laying down on the ice. My head-coach shakes his head at me, while the assistant coach nods approvingly and claps his hands. I am confused at the first response.

I did what I was supposed to.

I am completely distracted by my thoughts of whether or not I have gotten the approval of my coaches. Meanwhile…the player on the ice slowly gets up with the help of his coaches.

4. YOU’RE OUR RAY EMERY

“Ray Emery’s blackness also came to be seen as a ‘pollutant’ within the NHL, and the Ottawa Senators did their best to keep their gangsta goalie’s behavior in check” (Lorenz & Murray, 2011, 197).

Ever since I became interested in hockey I wanted to be a goalie. I was drawn to the unique equipment, the colorful leg pad, and unique helmet designs of all the different goalies in the NHL. I also grew up watching Martin Brodeur and Dominik Hasek and I was fascinated by how both these hall of fame goaltenders would flail body parts all over the ice in order to stop the puck. I wanted to be that guy. Yet it wasn’t until I was 22 years old that I started regularly playing goal. It was the best sport decision I ever made.

Playing goal was my calling…

I have been playing in this adult recreational league for about seven years now. I am currently playing on three different teams, and I am never short on offers to sub and obtain even more ice time. My body is needed. I am about to walk into the locker room of a team that I have subbed for many times. I like these guys. They are fun to play with and this should be a competitive game. Yet I never feel like I am completely relaxed in the locker room. It may be buried in a sea of other thoughts but I can never fully escape the worry that it might come up.

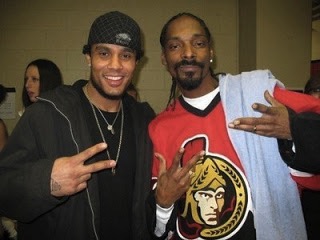

“I was talking to one of my students and he said, he doesn’t pay attention to hockey, because black people don’t play it. I said, wait a minute. We have our own dreadlock wearing Ray Emery on our team.”

FIGURE TWO-RAY EMERY (LEFT) AND RAPPER SNOOP DOGG.

There is no way this isn’t going to be awkward. Really awkward! I have been called out. Not me the human, but the brown skin of my body. What really causes those knots in my stomach though is the fact that I know I am about to be forced into an uncomfortable conversation about race with people who do not have a lot of experience talking about this issue or actually interacting with people of color.

I live in fear of moments like this. My actual job requires me to teach about racial issues in America and sometimes I just don’t always have the energy to be the teacher outside of the classroom, especially if I am the only racial minority present.

I enjoy talking about racial issues outside of the classroom, but not if I have to convince people that race matters and explain that racism is more than a dislike of a certain group.

The stress and nervousness I have at these moments is worse than any pre-game jitters. Not really knowing what to say to this comment I simply mention that Anson Carter also sported dreadlocks for a brief time in the NHL. I hope that my brief acknowledgement of the situation is enough to end it. “Don’t you know that it’s racist to say he is black”?

This is why I fear these conversations.

I’m sorry. I want to explain that it is not racist to say that Ray Emery, or myself is black, but it is an overwhelming task.

How do you have that type of conversation in a locker room? How do you say, that maybe its fear of having to deal with these types of moments that might push black players away from the game? If they think simply mentioning one’s race is racist, what will they think if they know I need Ray Emery? He looks like me and plays hockey. He knows what its like. How do we talk about race when it’s racist to mention race?

5. JUST BOYS BEING BOYS

It’s summer time, which means that league play is only once a week and I have to go to pick-up hockey at another rink in order to fulfill my hockey fixation. I feel fine once I step out on the ice, but here more than anywhere else, I always feel anxious upon entering the locker room. I don’t play on a team with any of these guys, I am always the only person of color, and I de-friended one of the regular players on Facebook after some of his comments about race and his posting of a pic of his white friend sticking his naked rear-end on a television screenshot of President Barack Obama’s face. Whether right or wrong I can’t stop thinking about how my body sticks out in this environment. I feel as though I am on display, and my anxiety heightens as I fixate on my perception that many of these guys don’t interact with racial minorities on a regular basis.

Today there is a beginner’s skills clinic going on before our session. One of the groups on the ice is a collection of women. These groups of women also have the locker room right next to ours. As the women file off the ice, a few of the guys decide now is the exact time they should use the urinals that are right in front of both locker rooms. Another player contemplates going to ask some of the women to help him get dressed. I feel like I have been transported back to my early teenage years. I find these antics to be sexist, but I do not speak out against them. In fact, while I know I disagree with what is happening at this moment, while these misogynistic discussions continue a feeling of calmness washes over me.

I am not the one on display. The gaze has shifted. In this moment it is clear that my body belongs. This behavior is reaffirming this space for me.

The gaze has shifted but the destructive forces remain in tact.

6. OF COURSE SHE WAS A BLACK WOMAN

Again, I find myself making the rounds as a goalie sub. No matter how many times I have played for this team, I still feel uncomfortable getting dressed and undressed in the locker room with them. On the ice, it is a different story. They have all played together for a long time and it is highly enjoyable to play with them on the ice. However in the changing room it just seems like we are all very different. I come from a place where there are a lot of people that look like me, but here I often feel like I am a unique encounter for them. There is nothing that verifies this, but I get a vibe. It makes me anxious. Nevertheless, they ask me to play and I am there. I just can’t say no to hockey.

Yeah, last year in that town a woman was pimping out her little sister”

Please, don’t let her be black. Please, don’t let her be black.

She was black” “OF COURSE SHE WAS!”

I should be angry, very angry, but it is not anger I feel.

It feels like my heart has jumped into my throat and the anxiety I feel is unbearable.

Breathe. Just breathe. You just need to finish getting dressed and get out on the ice. Get to the safe place. At this moment, I can’t engage with these statements. I don’t feel safe.

On the ice, my body does my talking for me. I feel safe out here standing in front of pucks flying from all directions. I can breathe out here. I can finally begin to think again and I try to process has what has just happened.

But I don’t want to think…I want to feel. How do I feel

7. A NIGHT TO REMEMBER

That legendary divorce is such a bore

As my bones grew they did hurt

They hurt really bad

I tried to have a father<

But instead I have a dad.

I just want you to know that I

Don’t hate you anymore

There is nothing I could say<

That I haven’t thought before

–Nirvana

It is early September in the year 2000. I haven’t spoken to my father in a year but we live in the same house. The last time we talked resulted in us shouting back and forth until my mom intervened. Why would I want to talk to him? He is a drunk, he hardly works, he leaches off of my mom, he is completely absent from any form of parenting, and when he does talk it is only to say something negative or for him to voice what he perceives to be my sisters or my personal failings. He serves no purpose to me. He is simply a presence I seek to avoid.

He is a prime source of my anger and my sadness.

I am making my way back home from hockey practice in my rusty (but beloved) 1994 Ford Escort. As I approach my street I see flashing lights everywhere. As I pull up my street I see five police cars parked alongside my parent’s house.

What is going on?

I park in front of our next door-neighbor’s house, grab my hockey bag and sticks, and I then make my way into the house. I hear sounds in the living room. I see my mother sitting on the couch crying, while one of her good friends tries to console her. My sisters are on the couch looking lost. Through her tears my mom tells me that her and my father (who was drunk) had pulled into the driveway and started arguing.

As both of my parents exited the car, my father proceeded to punch my mom in the face. She got away and into a neighbor’s house. “I think we might get a divorce. What do you think?” my mom says.

What do I think?!

I tell my mother I think this moment has been building for a long time. At this moment, looking at my sisters and mother, I feel like I should be overcome with sadness or anger, but right now I am filled with a sense of relief and joy. The dark cloud that has been surrounding me for almost forever is now gone. I don’t have to worry about interacting or engaging with him anymore.

But the effects of my father’s relationship with my family are by no means gone. In fact, they are going to shape the rest of the family’s relationships and personal identities for a while to come.

Years later I realised this moment was a turning point for me.

What if I had come home from practice ten minutes earlier? What if I had witnessed this act Would I have used my hockey stick and body as a weapon? Would the body I use to inflict physicality on the ice become a vehicle to release all the anger and sadness buried in me?

It took the loss of my father for me to learn what it means to be a man. To learn what it means to be a black man.

To heal men must learn to feel again – bell hooks

To know me, you have to know hockey.

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Alexander, B. (2006) Performing black masculinity: Race, culture, and queer identity. Lanham, MD: Rowman & Littlefield Publishers Inc.

Allen, K., Brady, E., & Hampson, R. (2012) Tweets put focus on racism, hockey and Boston. USToday.com Viewed 9 November 2015.

Denison, J., & Markula, P. (2003) Moving writing: Crafting movement in sport research. USA: Peter Lang Publishing Inc.

hooks, b. (2004) The will to change: Men, masculinity and love. New York, NY: Atria Books

Joel Ward not letting tweets ruin win (2012) Espn.com. Viewed on10 November 2015.

Lorenz, S., and Murray, R. (2011) The Dennis Rodman of hockey: Ray Emery and the Policing of Blackness in the Great White North. In Commodified and Criminalized: New Racism and African Americans in Contemporary Sport. Lanham: Rowman & Littlefield Publishers, Inc.

Nirvana, Serve the Servants Lyrics, In Utero Minnesota: DGC Records, 1993

MiksUn96. P.K. Subban almost killed Brad Marchand”. YouTube video, 2:04. Posted May 29, 2011.

P.K. Subban Collection of Racist Tweets. Digital Image. Turtleboysports.com. Viewed November 5th, 2015.

Ray Emery and Snoop Dogg. Digital Image. Vancouversun.com Viewed November 5th, 2015.

Richardson, L. (2000) New writing practices in qualitative research, Sociology of Sport Journal 17: 5-20

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivs 3.0 Australia License.

ISSN: 2202-2546

© Copyright 2015 La Trobe University. All rights reserved.

CRICOS Provider Code: VIC 00115M, NSW 02218K